May 18, 2022

MANILA – Throughout the campaign period, the achievements and programs of the late dictator Ferdinand Marcos Sr.—whether based on historical records or mere claims by die-hard supporters—seemed to have become the shadow of presumptive president Ferdinand “Bongbong” Marcos Jr.

The so-called legacies of the late Marcos have resurfaced amid the younger Marcos’ presidential bid. Stories glorifying and lauding what Marcos Sr. has done as president have spread online through various platforms—boosting the son’s campaign.

Many of these stories, however, have been fact-checked and found to be myths or false claims.

Among the myths swirling around the Marcoses, which have been posted and shared online by their supporters, was the story about Nutribun.

GRAPHIC: Ed Lustan

In this article, INQUIRER.net will present the facts about the Nutribun program, detail the revival of the iconic nutrition program that led to the brand in the 1970s, and who might benefit from a similar project if the presumptive president decided to implement it.

Popular again

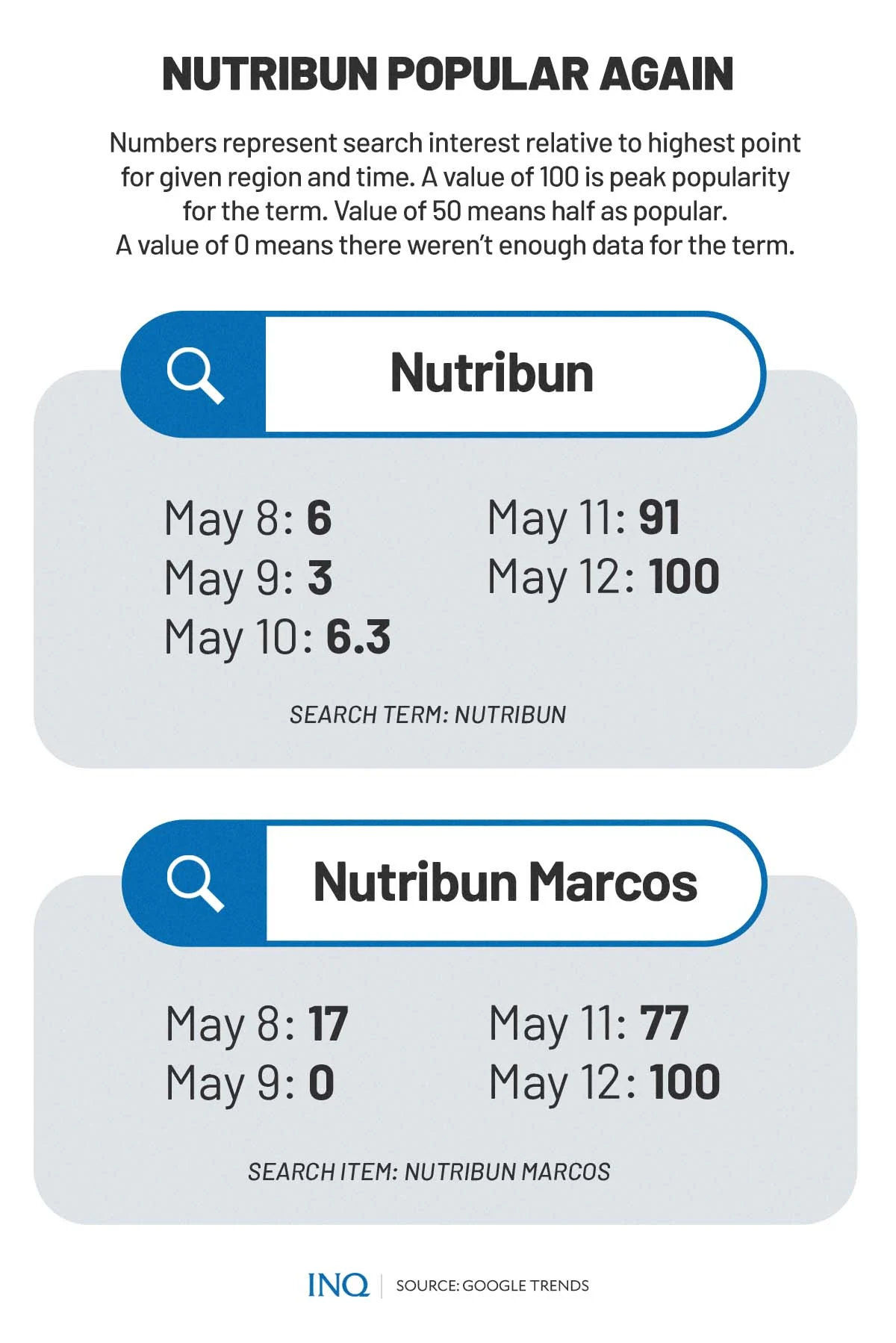

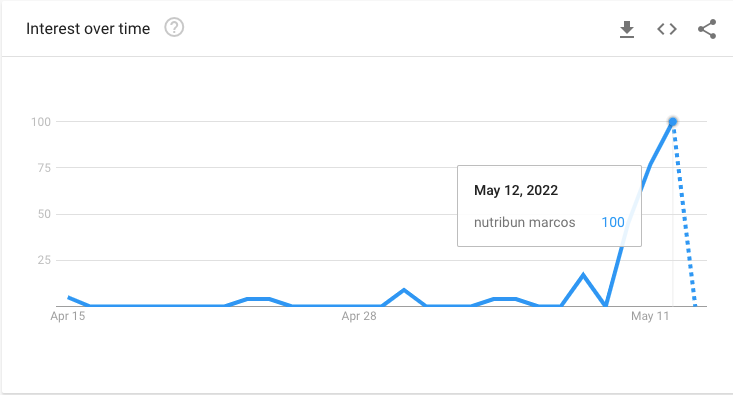

Following the general elections last May 9, as Marcos become the clear winner in the presidential race, the term “Nutribun”, “nutribun”, and “nutribun marcos” have gained more search hits than the usual, according to data by Google Trends.

Google Trends figures showed that the interest of people in the Philippines over Nutribun has steadily increased after the polls.

GRAPHIC: Ed Lustan

“Numbers represent search interest relative to the highest point on the chart for the given region and time. A value of 100 is the peak popularity for the term,” said Google Trends.

“A value of 50 means that the term is half as popular. A score of 0 means there was not enough data for this term,” it added.

The term “Nutribun,” for example, reached its peak popularity on May 13.

GRAPHIC: Google Trends

On the same day, partial and unofficial results from the Commission on Elections (Comelec) Transparency Media Server showed that Marcos already has a total of 31,104,175 votes.

Here’s what the search activity among Filipinos, who looked up the term “Nutribun” online looked like, based on Google Trend’s interest over time criteria.

May 8 score: 4

May 9 score: 2

May 10 score: 43

May 11 score: 63

May 12 score: 67

May 13 score: 100

The term “nutribun” also gained more Google searches after the elections.

GRAPHIC: Google Trends

May 8 score: 6

May 9 score: 3

May 10 score: 63

May 11 score: 91

May 12 score: 100

Filipinos across the country also searched for the term “nutribun marcos.”

GRAPHIC: Google Trends

May 8 score: 17

May 9 score: 0

May 10 score: 45

May 11 score: 77

May 12 score: 100

Both the terms “nutribun” and “nutribun marcos” had peak search hits on May 12, a day after the camp of former senator Marcos declared victory in the presidential elections.

“With 98 percent of the votes counted, and an unassailable lead of over 16 million votes, the Filipino people have spoken decisively,” Rodriguez said in a statement, citing Comelec’s partial and unofficial count.

“Ferdinand ‘Bongbong’ Marcos Jr. will be the 17th president of the Philippines. In historic numbers, the people have used their democratic vote to unite our nation,” he added.

As the topic became trending online, a simple Facebook search using the same terms will lead you to posts claiming that Nutribun was a project of the former dictator.

PHOTO: Facebook

On May 12, a Facebook page posted graphics stating that free Nutribun will soon return, showing pictures of both Marcos Sr. and Marcos Jr.

Was it a Marcos project?

A Facebook post, meanwhile, showed a picture of the Marcoses distributing what looked like Nutribun in an unidentified school.

PHOTO: Facebook

The post said the late dictator has fed many starving mouths. It also attributed Nutribun to Marcos, saying that the iconic bread would’ve not reached Filipinos if not for Marcos.

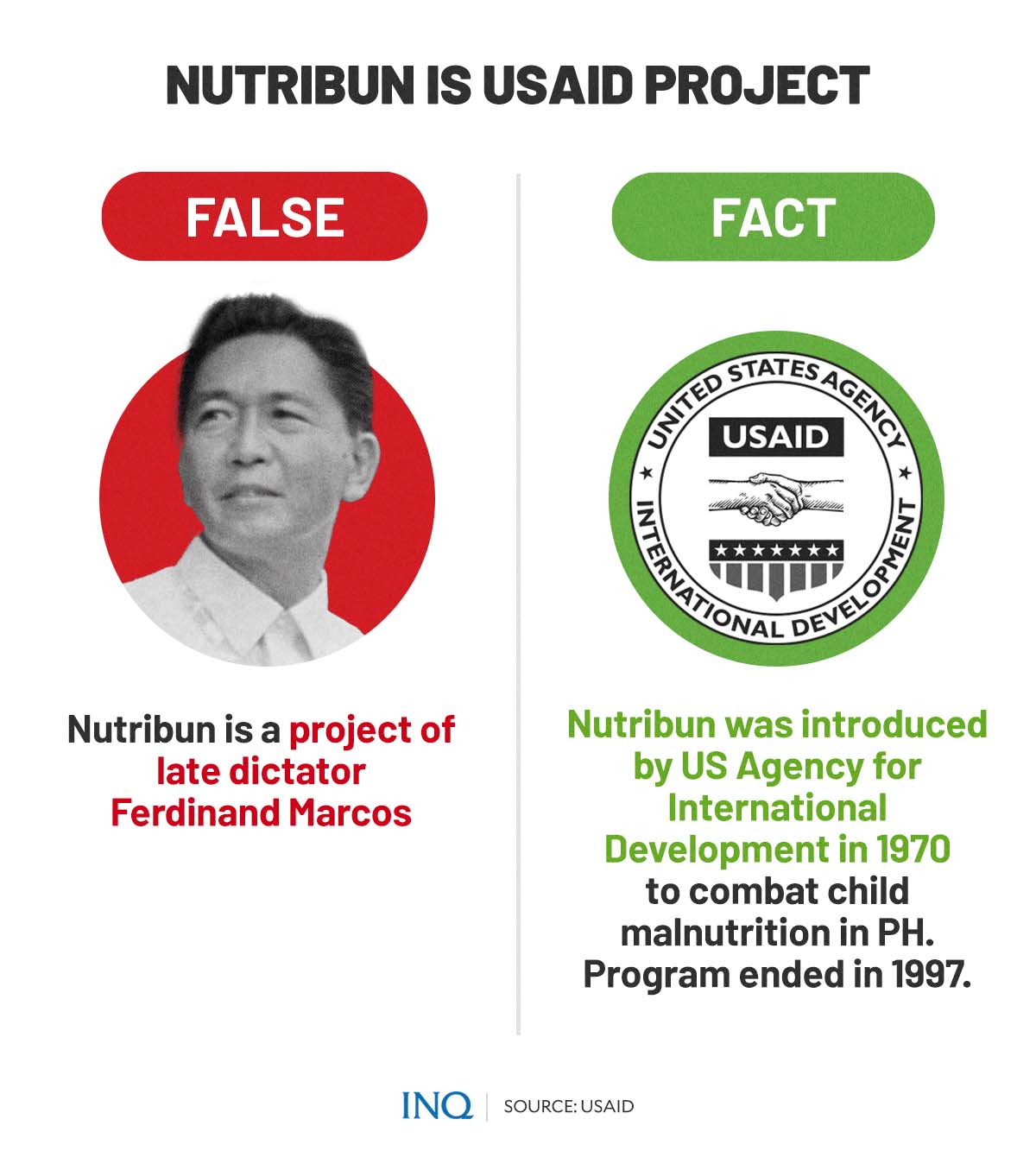

But is Nutribun an original project of the Marcoses? The short answer is: No.

Nutribun was first introduced to the Philippines in the 1970s in collaboration with the US Wheat Associates and was designed as a convenient “ready-to-eat and complete meal” for public elementary school feeding programs to combat child malnutrition in the Philippines.

“USAID (United States Agency for International Development) Nutrition was responsible for development of the formula to justify a claim for nutritious snack food,” said a 1979 document made available online by the same US humanitarian body.

“It was also in 1970 that USAID made its decision to combine its Food for Peace and its nutrition activities and to target its food donations to the malnourished child population,” the report by the mission’s chief of party Dr. Reuben William Engel stated.

“Through operational research support to Catholic Relief Services and Foster Parents, the AID nutrition office had developed a methodology for a Targetted Maternal Child Health Program and had begun testing the Nutribun, a ready-to-eat bakery-bun snack food for school children,” it continued.

In the July 1973 issue of the War on Hunger, American historian Paul E. Johnson wrote that “the testing and development of soy fortified bread flour was undertaken primarily by Dr. C.C.Tsen and Dr. William J. Hoover of the Food and Feed Grain Institute of Kansas State University. Working under an AID contract, begun in 1967, to improve the nutritive value of cereal-based foods.”

Johnson explained that the objective behind Nutribun was to develop a bread containing 12 percent soy flour—which is “virtually indistinguishable from white flour bread–in texture, color, taste, loaf volume, or other traits”—and is high in protein and relatively inexpensive to produce.

Engel detailed in the report that each bun is made with the following main ingredients: flour (soy fortified), water, yeast (active dry), salt, sugar (fine granulated), and oil.

Nutribun—which usually weighs around 170-190 grams, heavier than the regular pandesal which typically weighs 25-30 grams—also contains calories, protein, calcium, iron, and other nutritional ingredients such as:

- Vitamin A, which according to the US National Institutes of Health (NIH) is important for normal vision, the immune system, reproduction, and growth and development.

- Ascorbic acid, also known as Vitamin C, which is necessary for the formation of blood vessels, cartilage, muscle and collagen in bones and is vital for the body’s healing process.

- Thiamine, or Vitamin B1, which allows the body to help convert food into energy.

- Riboflavin, also known as Vitamin B2, which helps break down carbohydrates, proteins, and fats to produce energy.

- Niacin, Vitamin B3, a vitamin which helps keep a person’s nervous system, digestive system, and skin healthy.

“The local commercial bakeries formulated and blended local and donated ingredients, and baked and delivered the Nutribuns to the schools. The schools reimbursed the bakeries for the cost of local ingredients and their services. Pupils were asked (but not forced as a condition of participation) to share these costs,” the report said.

A report published by Vera Files in 2020 entitled “Marcos propaganda in a time of plague,” said that Nutribun—contrary to popular claims—was not given to children for free.

The buns were first sold to students for 10 centavos each. The price then increased to 25 centavos by the mid-1980s. Students who are very poor and cannot afford the buns were provided sponsors, according to the report.

According to the USAID document, the Nutribun program filled the tummies of a total of 1,300,000 elementary school pupils during the 1971-1972 school year. It continued to become a crucial part of the government’s—led by Marcos—action against malnutrition in the Philippines.

The calorie and protein-packed bun program was discontinued in 1997 to make way for more forms of feeding programs.

Attaching it to the Marcos name

If the Nutribun was a USAID program, then why do some people credit the Marcoses for it?

Engel stated in the USAID report that the Nutribun program coincided with Project Tulungan, which was organized and led by then-first lady Imelda Marcos. It was through the private entity that the USAID Nutrition Office was able to collaborate with the USAID Population Office in Manila.

GRAPHIC: Ed Lustan

“In 1970, following the initial efforts to integrate nutrition and family planning through a private entity (project Tulungan), the USAID Nutrition Office collaborated with the USAID Population Office in Manila to explore the possibility of delivering family planning services through the Targetted Maternal Child Health Program and through government programs planned at provincial level,” said Engel.

“The project represented a first major effort to combine nutrition and basic health services with family planning services, initially in the Manila and other city slums and later extended to rural areas as well,” he added.

However, it was during a disaster when the Marcos administration did the unthinkable and claimed the Nutribun project as its own.

On July 12, 1972, Marcos Sr. placed the entire Luzon under “a state of public calamity” after Typhoon Gloring—international name: Rita—caused intense flooding from July 10-25, which resulted in the deaths of at least 543 people—according to a report by the United Press International (UPI).

It was during this crisis, dubbed the “Great Luzon Flood of 1972,” when Nutribun gained greater popularity as millions of buns were—as described by Dr. Grace Goldsmith in the journal International Nutrition in 1974—“airdropped” to people in areas that were hardest-hit by the calamity.

In a memoir entitled “My 17 Years with USAID: The Good and the Bad,” Nancy Dammann wrote: “the Nutribun bags were being stamped with the slogan ‘Courtesy of Imelda Marcos–Tulungan project’.”

Dammann said the wives of some American officials helped package rice and Nutribuns, which were later on distributed to flood victims. She added that aside from the first lady’s name, the food packages were also stamped with the names of provincial politicians.

American journalist Lee Lescaze, according to a report by Vera Files, wrote something similar to Dammann’s statement in an August 1972 syndicated column.

“Plastic bags stamped with her name were being widely used at one time for relief grain distributed in central Luzon’s most-damaged villages,” Lescaze said.

Revived project

Although the Nutribun project ended decades ago, there have been several times when the vitamin-enriched bread of the 1970s was revived to fill the tummies of children in the Philippines.

In 2014, then Manila Mayor Joseph Estrada brought back the Nutribun program to address persistent malnutrition among children in the city.

In March 2020, San Miguel Corp. (SMC) announced that it will start the production of Nutribun, which was aimed for distribution to charitable groups and critical Metro Manila communities where families have either no access to, or unable to afford, food amid the coronavirus (COVID-19) pandemic.

SMC was able to initially produce 10,000 buns per day. The production volume increased to 24,000 pieces of Nutribun daily in April with the help of SMC’s subsidiary San Miguel Foods Inc.

The SMC-produced buns weighed 85 grams and contained 250 calories.

Later that year, on July 29, the Department of Science and Technology’s Food and Nutrition Research Institute (DOST-FNRI) soft-launched the Enhanced Nutribun—which is similar to the 70’s bread, except it has more micronutrients like iron and vitamin A, softer in texture, and weighs 160-165 grams per bun.

Data from the DOST-FNRI detailed that each serving of Enhanced Nutribun has 504 calories, 17.8 grams of protein, 6.08 milligrams of iron, and 244 micrograms of vitamin A.

The Enhanced Nutribun was developed to address the still-growing issue of malnutrition in the country, especially amid the ongoing global health pandemic caused by COVID-19.

“The Nutribun is an example of a science-driven solution that government is pursuing to address hunger and malnutrition. The Enhanced Nutribun developed by DOST-FNRI is more delicious, more nutritious, has better texture, made mainly from squash for better taste, and enriched with protein, iron and vitamin A among others,” said Cabinet Secretary Karlo Nograles.

The first variant of Enhanced Nutribun released by the DOST-FNRI was the squash variant, which the agency said is rich in fiber, energy, protein, calcium, potassium, iron, zinc, and vitamin A and has no trans-fat, cholesterol, artificial flavor, or food coloring.

The following year, the DOST-FNRI launched the carrot variant in April and the sweet potato variant in October.

This year, two new variants were introduced to the public: the purple sweet potato variant and the orange variant.

Feed the PH children

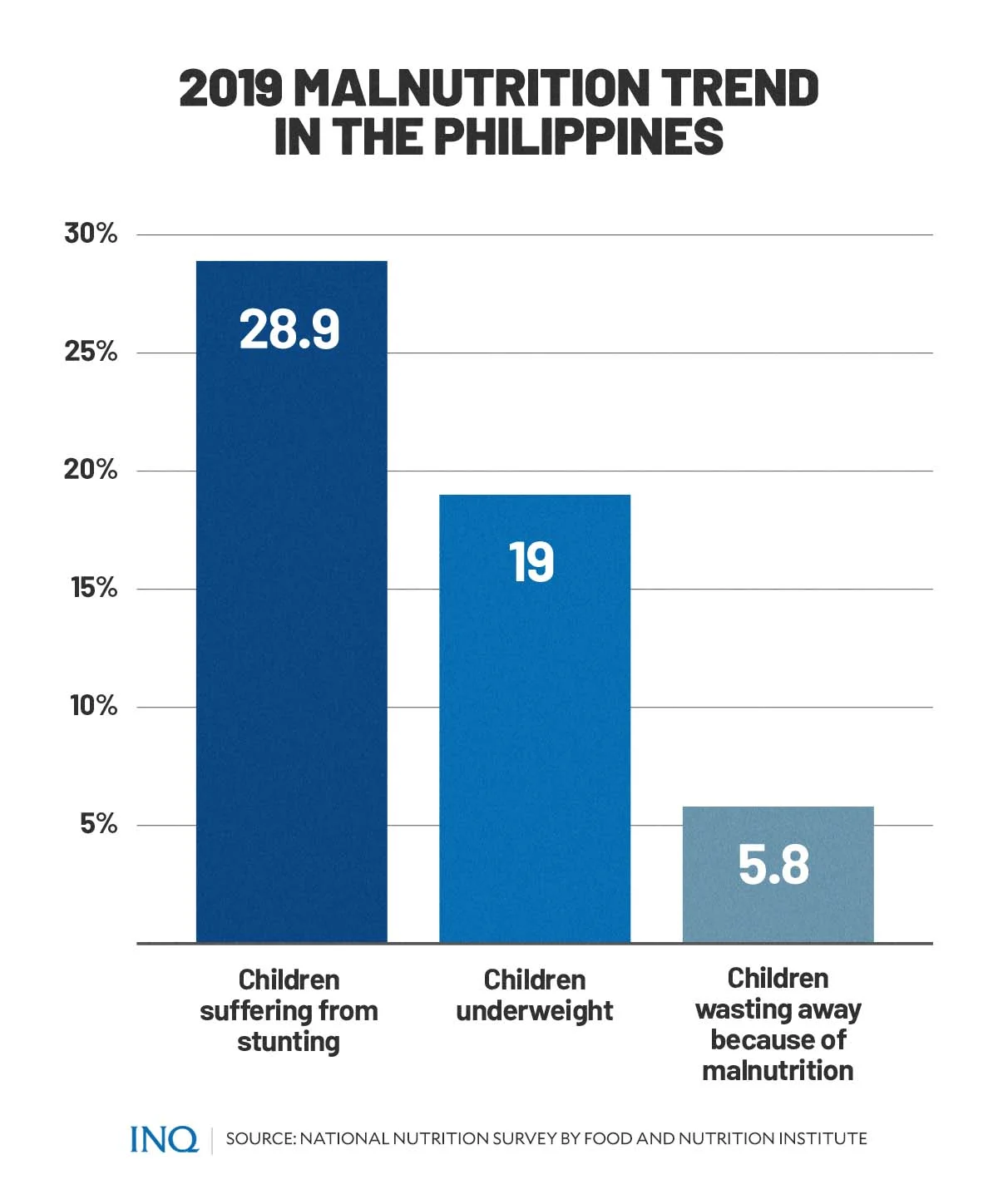

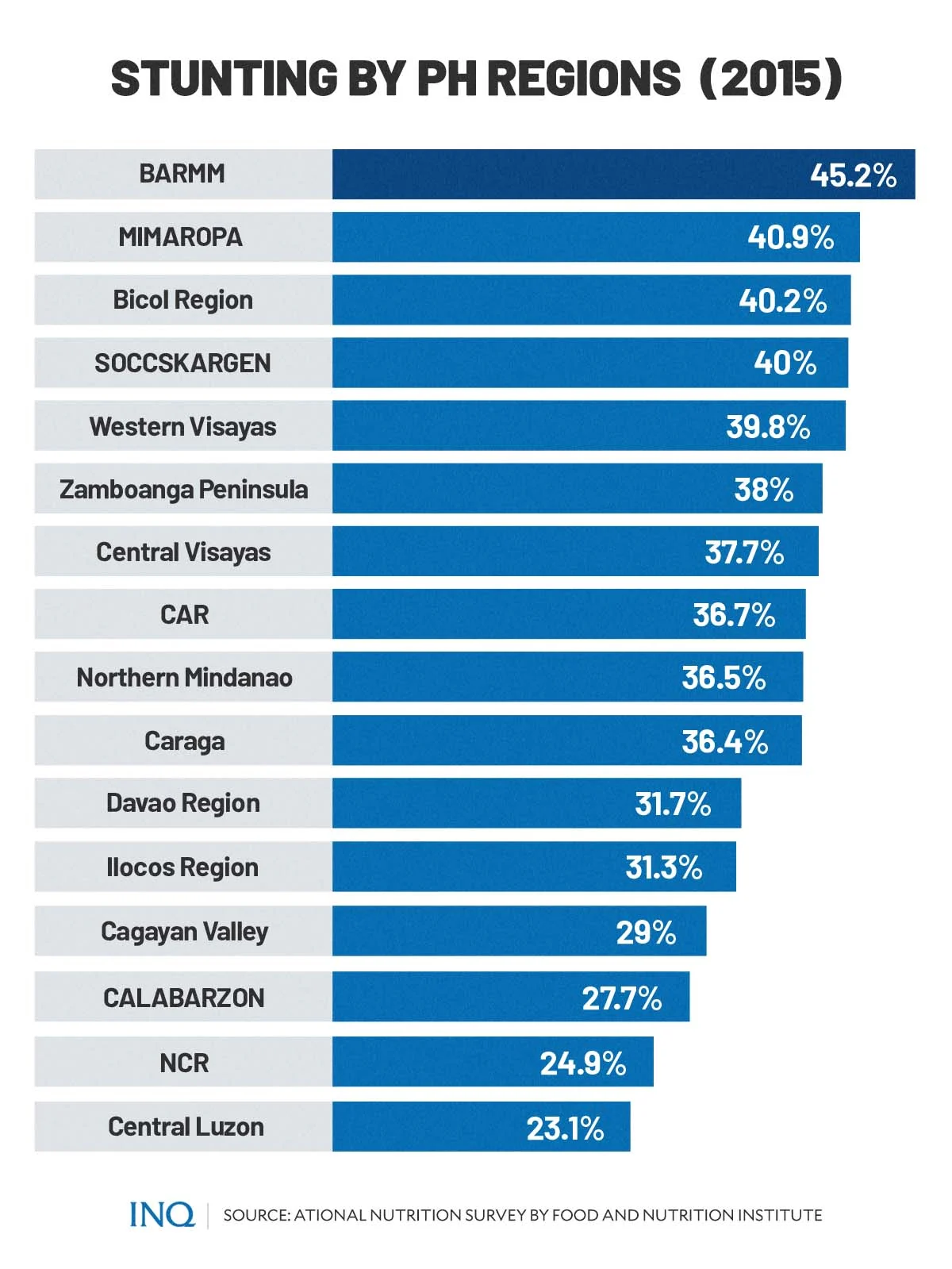

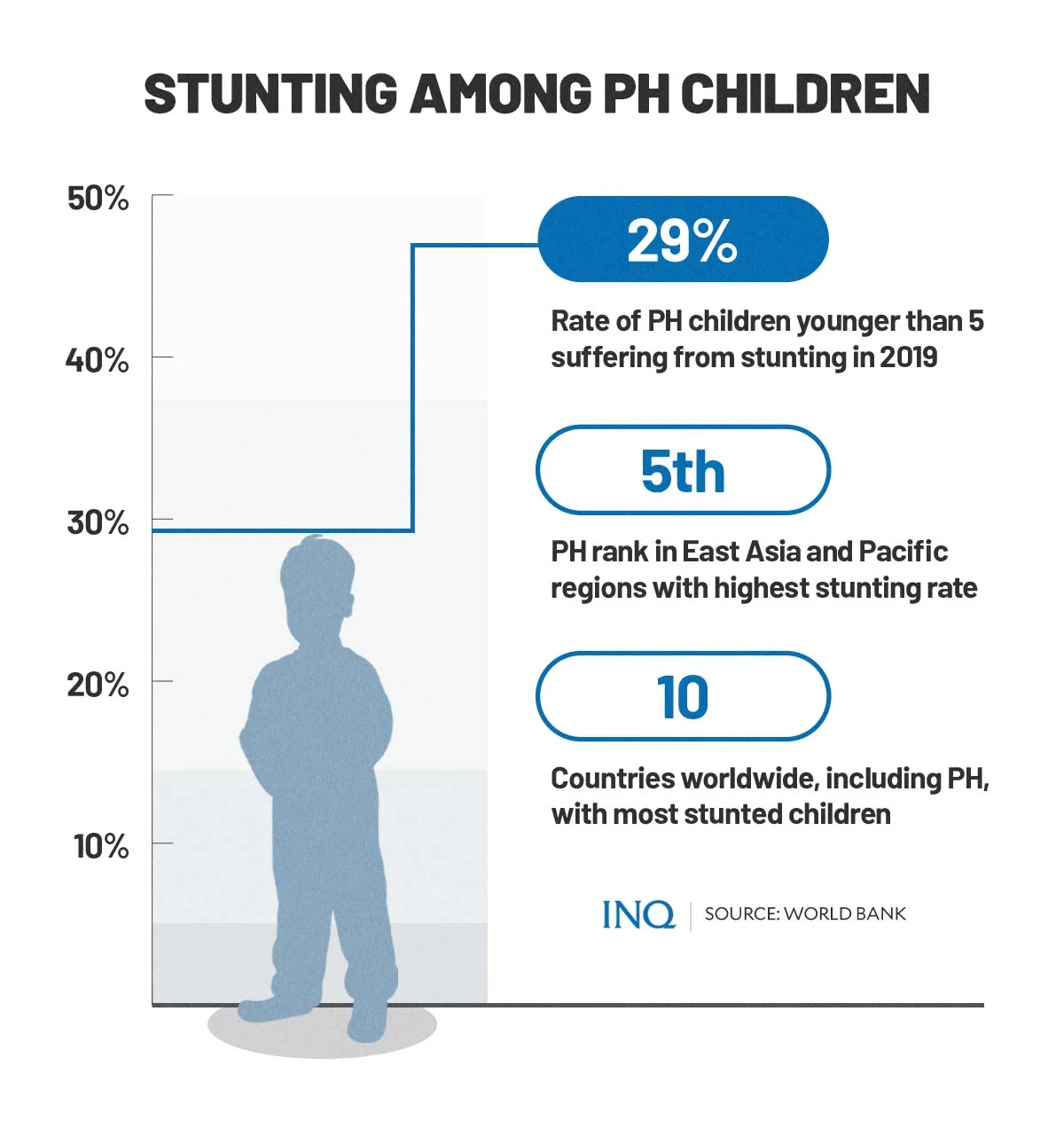

Based on data by the World Bank, 1 in 3 children—29 percent—in the Philippines younger than 5 years old suffered from stunting in 2019. Stunting, as defined by the World Health Organization (WHO), means that the height of a child or individual is low for his or her age.

GRAPHIC: Ed Lustan

Meanwhile, 19 percent of the Filipino children under the same age group were found to be underweight during the same year. Around 5.8 percent weighed too low for their height.

One of the key drivers of malnutrition among Filipino children, according to World Bank, was poverty. Other underlying determinants included poor access to health services, inadequate access to diverse, nutritious foods, and inadequate care and nutritional practices for women.

GRAPHIC: Ed Lustan

A 2019 study by the DOST-FNRI showed that the rate of stunting, malnutrition, and wasting in Filipino children under age 5 was highest among those who are part of the poorest population.

Around 42.4 percent of children were stunted, 27.3 percent were underweight, and 7.6 percent were wasted.

Among the children below 5 years old living in poor communities, 32.4 percent were stunted, 21.4 percent were underweight, and 5.1 percent were wasted.

GRAPHIC: Ed Lustan

Nutribun, if distributed at a very low or affordable price, could help address the malnutrition issue in the Philippines.

Should Marcos Jr. decide to make Nutribun a program under his administration—if the buns were to be distributed at a very low or affordable price—many Filipino children would benefit from it and get the nutrients their bodies need.