January 12, 2023

MANILA – As the government scrambles to find ways to bring down prices of onion in the market, several reasons have emerged for the soaring prices of the staple vegetable.

For months, the price of red and white onion in the country has been continuously increasing.

The Department of Agriculture’s (DA) price monitoring showed that as of January 10, red and white onions were being sold for P420 to P600 per kilogram—above the suggested retail price of P250 per kilogram set by the Department of Trade and Industry in December last year.

GRAPHIC: Ed Lustan

The current prices were also way higher than P200 per kilogram recorded on the same day last year.

As onions continued to sell at prices greater than a day’s worth of minimum wage, several possible reasons have been made as to why prices of the vegetable began to shoot up last year.

In this article, INQUIRER.net revisits these statements by the agriculture department, officials, and experts.

‘Onion cartel’

On Monday, Senator Cynthia Villar said a cartel might be behind the current spike in onion prices in the local market. She explained that a previous investigation in 2013 uncovered an onion cartel manipulating the supply and price of onions by creating “artificial demands.”

“At times, it is this cartel that has been creating artificial demand to allow [an] increase in demand and they will control the supply, so that is what we need to address,” she said.

In an interview, Assistant Agriculture Secretary Rex Estoperez said the department is set to meet to discuss the continuing spike in onion prices, including the claim made by Villar about an onion cartel.

Last December, the DA aired suspicion that a crime syndicate could be hoarding supplies of red onions, which were bought at a cheaper price during the harvest season.

Marikina Rep. Stella Luz Quimbo had filed House Resolution No. 681, which calls for an investigation into the alleged cartel and anti-competitive practices in the onion industry amid the still-increasing prices of onions in the local market.

Quimbo noted that allegations of an onion cartel controlling supply and the possibility of hoarding white onions had been flagged by citizens and policymakers as early as August 2022.

Over the weekend, Sen. Sherwin Gatchalian said that the government should create a task force led by the DA to investigate traders and hoarders who could be manipulating the price of onions in the country.

Supply shortfall, other factors

Some lawmakers and experts have also attributed the exorbitant price of onions to supply shortage.

As early as August, agriculture officials have already warned of a possible shortage supply as the sufficiency level for red onions in Central Luzon, Calabarzon, and Mimaropa—the top onion-producing regions in the country—fell to 0 percent in July.

The DA estimated that the stock of red onions might be scarce until November.

Local onion producers in Nueva Ecija have also warned that they have already run out of white onions in their storage facilities in July.

While the harvest season varies per province, onions are usually harvested between February and April or around four months from the time they are planted between November and January.

According to Raul Montemayor, national manager of the Federation of Free Farmers (FFF), the supply of harvested onions usually begins to dwindle in the last quarter of the year and is “normally augmented by imports.”

“On average, we produce only 80% to 90% of domestic demand, so there is an annual shortfall that needs to be filled up by imports,” Montemayor told INQUIRER.net.

“If local production drops due to infestation, pests, weather disturbances, or decreased plantings, and imports do not come in on time to fill up the gap, prices will go up, and this is probably what has happened,” he added.

Failure to import

Montemayor noted that the supply shortfall and the increasing prices of onion were exacerbated by the DA’s decision to “curb imports” in the latter part of 2022, along with the alleged price manipulation by traders “who took advantage of the supply situation.”

In December, when the price of onion reached P600 a kilo in public markets, the DA stressed that it was not considering allowing the importation of the commodity since the country still had enough supply.

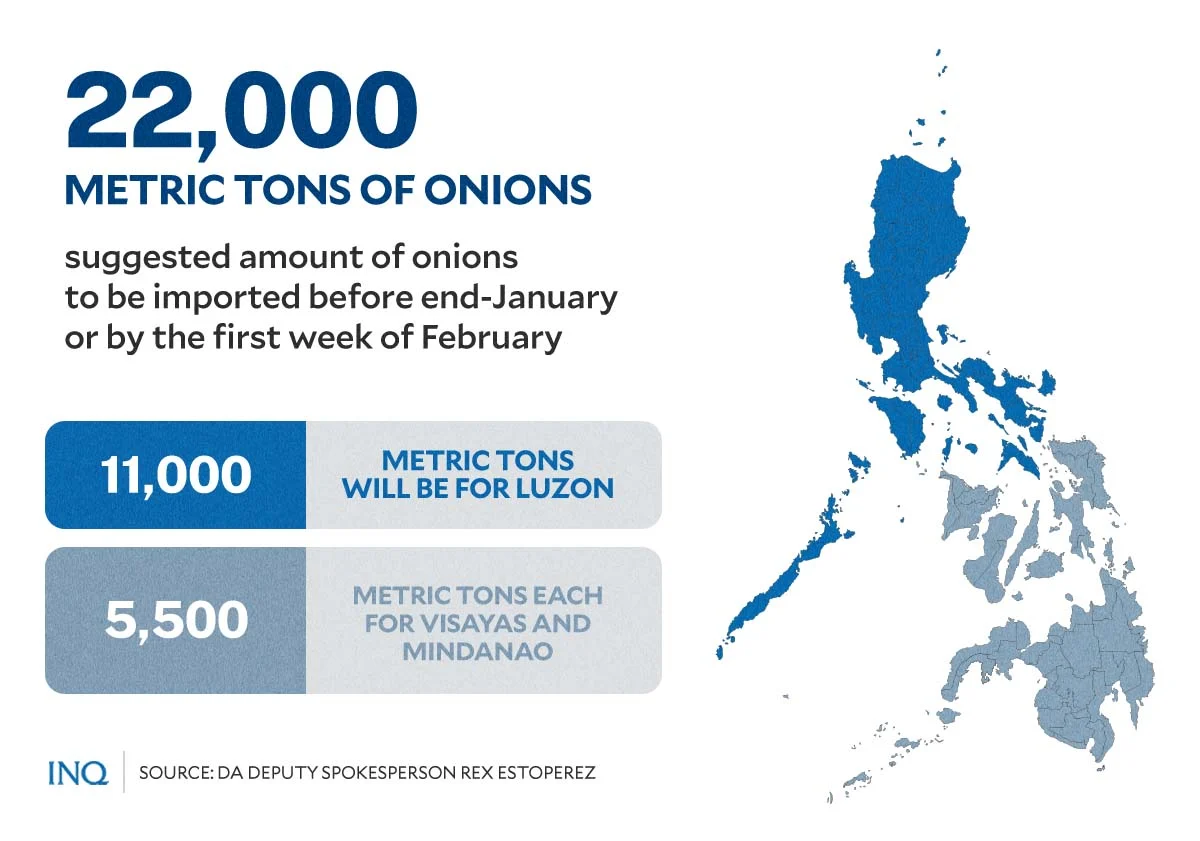

GRAPHIC: Ed Lustan

The department previously said the government was considering the importation of 7,000 metric tons of red onions to stop the spike in the cost of the commodity but that this would be made only if there was indeed a shortfall.

“As of now, we are not considering the importation of agricultural goods, especially onions. We know there is an imperfection in our system. We will need to provide better interventions, especially in the value chain,” Estoperez said last month.

“[W]e have enough supply but just enough to meet our requirement.”

More investigations underway

The Office of the Ombudsman has summoned officials of the DA and the Food Terminal Inc. (FTI) for an investigation over the alleged procurement of some P140 million worth of onions from a Nueva Ecija cooperative.

The DA, which President Ferdinand Marcos Jr. concurrently heads as secretary, and the FTI will be asked to explain the procurement process of onions worth P537 per kilo from Bonena Multipurpose Cooperative.

A report by the Philippine News Agency noted that the same onions purchased by the DA and FTI were sold at only P170 per kilo at the government-run Kadiwa store.

The investigation was first reported over dzBB early last Tuesday. Estoperez confirmed later that day that some officials of the agency had already received summonses.

“We will check if there is a collusion, if there is a conspiracy between some officials of the Department of Agriculture and the private sector,” Ombudsman Samuel Martires said in a radio interview over dzBB last Wednesday.

“We have to wait for the explanation of FTI. Why did they purchase onions from this cooperative?” he added.

Martires said they will ask Agriculture Undersecretary Domingo Panganiban to explain why the agency and FTI bid at that price and the decision to import the produce when the local harvest season is about to start.

What we should keep in mind

Amid the confusing and contradicting barrage of statements by officials and experts explaining the possible reasons for the high onion prices, Montemayor reminded consumers that the issue is not due to high prices being demanded by farmers.

Farmers, Montemayor added, actually sell produce at very low prices to traders during harvest season.

“Consumers, and the government, have to realize that farmers need to earn from their livelihood, recover their costs, and have enough left to support their families,” he said.

“If we focus only on keeping prices low to control inflation, and in the process put a lid on farm gate prices or even drive them down through SRPs or excessive imports, then we will end up discouraging farmers from planting,” he added.

TSB

(Next: Government solutions: Importing onion, setting SRP, selling smuggled onions—are these enough?)

Read more: https://newsinfo.inquirer.net/?p=1715362#ixzz7q8ujyrBQ

Follow us: @inquirerdotnet on Twitter | inquirerdotnet on Facebook