March 14, 2023

TOKYO – When a natural disaster such as a strong earthquake occurs, people with physical or mental disabilities can face special difficulties, as shown in the fictitious scenario below. It is essential to prepare systems to help such people evade danger, evacuate quickly and reach accommodation shelters smoothly. However, observers say efforts geared to these ends are currently lacking. In recent years, ties within local communities have been weakening, and it is hoped that people with disabilities can be enabled to help themselves. In times of crises, taking refuge at home is being eyed as an option if safe evacuation is out of the question for such people.

1. Rattled by an earthquake while at a coffee shop

Hanako, 40, has difficulty walking because she was injured in a traffic accident 10 years ago.

She uses a wheelchair and lives alone in an apartment in Tokyo. Hanako works at an office on weekdays, and she likes going to cafes.

One afternoon on a weekend, Hanako was having tea with a female friend from college, also 40, at a fashionable coffee shop in her neighborhood. Just as Hanako took a bite of cake, a strong earthquake occurred. Mugs and lights in the cafe shook violently.

“Watch out! Protect your head!” Hanako shouted to her friend, fearing that something might fall. Her friend immediately protected her head with her handbag, which was next to her.

Hanako’s bag was hanging on the back of her wheelchair. Since Hanako could not get under the table, she covered her head with her hands.

The earthquake finally stopped. Fortunately, neither of them was injured. Glasses and plates that had fallen from shelves were broken and scattered around the place. Coffee shop workers were rushing about in confusion.

Hanako thought she should go home and check her apartment, and her friend said she was worried about her cat. They left the coffee shop, promising to call each other if anything happened. Hanako started to head home.

2. Neighbors help with return to second-floor apartment

Hanako lives on the second floor of an apartment building. When she arrived in the lobby, she found the elevator was not working. There was no sign of movement even when she pressed the up button. “The elevator must have stopped because of the earthquake. It may not work again for a while if it is out of order,” she thought. Although there is a stairway, it was difficult for Hanako to return home on her own.

She was at a loss about what to do. Then, a young couple who live in the same building asked her if there was a problem.

When Hanako told them that she wanted to return to her apartment because she was worried about its condition, the couple asked three male residents who were in the lobby if they could help Hanako get to her apartment. They offered to help her get to the second floor.

One of the three men happened to work at a welfare facility and had experience assisting a wheelchair user in going up a staircase as part of an emergency drill.

Although the staircase was seldom used, it seemed to be undamaged. Since it seemed like there would be no problem using the staircase, the men, encouraging each other, grasped the front and back of the wheelchair, carefully lifted it and went up the stairs step by step.

After they reached the second floor, Hanako bowed deeply and said to them: “Thank you for helping me in this difficult time.” Hanako then opened to the door to her home.

3. A sister’s helping hand, and a dark night alone

Hanako’s one-bedroom apartment has a living room and a dining and kitchen area. She was able to enter her home and go through the hallway because no objects had been placed there.

However, the living room was a completely different situation. A cupboard’s doors were open, and many dishes were on the floor, broken. Bookshelves were leaning against the table, and books had fallen from them.

Hanako realized that she could have been injured if she had been at home when the earthquake occurred, and she regretted not having taken anti-quake measures such as securing the furniture.

Concerned about the safety of her sister, 35, who lives with her family nearby, she contacted her sister via smartphone.

Relieved to hear that they were safe, Hanako explained to her sister the situation at home and asked her if she could come over to help. Her sister soon came to Hanako’s apartment and helped clean up. Before leaving, Hanako’s sister told her to call anytime if she needed something.

Hanako thought about what she should do next. Fortunately, she had about three days’ worth of food and water. Once the elevator was running again, she would be able to leave the building.

Since she had no items like batteries at home, Hanako felt uneasy about staying in an apartment without electricity. She wondered if she should go to an evacuation center.

After a while, Hanako received a message from a friend who also uses a wheelchair. Her friend went to an evacuation center, but did not feel comfortable there. Thinking that she would not get sufficient support at an evacuation center, Hanako spent the night at home in the dark.

Helping disabled people evacuate in disaster

When a disaster hits, everyone is affected, including disabled people.

In the 2011 Great East Japan Earthquake, the mortality rate among physically or mentally challenged people in the three prefectures hit hardest by the quake was about twice as high as the figure for all those affected.

Helpers and caregivers were also affected by the quake, which might have caused people who required assistance to be unable to evacuate quickly.

Disabled people and disaster response was an important agenda item at the U.N. World Conference on Disaster Risk Reduction held in Sendai in 2015. The conference discussed such issues as the need to compile evacuation plans based on the points of view of the disabled community. These talks gave rise to the concept of “inclusive” disaster management, in which nobody gets left behind.

Hurdles to clear

Doshisha University Prof. Shigeo Tatsuki, an expert in welfare and disaster prevention, said people tend to gravitate to spaces next to walls when evacuating to large-scale shelters, such as school gyms, when disaster strikes.

If shoes or other possessions are scattered around entrances, or baggage is placed in aisles, wheelchair users and visually impaired people can find it hard to move around.

It can also prove difficult for such people to join lines for food handouts or to queue to use a bathroom. For people with developmental disorders, private areas can help relieve anxiety.

Self-help

Atomi University Prof. Hajime Kagiya, another expert on welfare and disaster prevention, said: “It’s not necessary to take risks to reach a shelter. I recommend that [disabled people] shelter at home, where they are accustomed to living.”

Kagiya only recommends this option after people weigh possible or urgent dangers, such as an approaching tsunami.

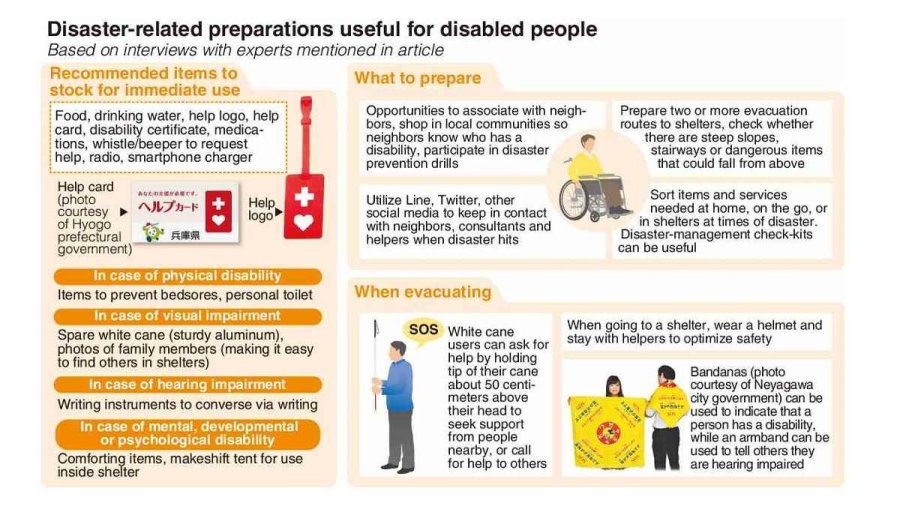

He also advises stocking up on supplies that can last for three to seven days, should disaster strike. As power and running water may be adversely affected when a calamity unfolds, food, drinking water and spare batteries, among other items, need to be prepared. Portable toilet items should be prepared based on an assumption that each person will use such items five times a day.

Masayoshi Togashi, an incident response caregiver of the Nippon Care-Fit Education Institute, said: “Ideally, disabled people should keep in contact with residents in their respective local communities so as to prevent becoming isolated at home. Doing so will let neighbors know the kind of help disabled people might need [in the event of disaster].”

Togashi added that if everyone participates in disaster prevention drills, it can help raise awareness among people in the local community. Some residents even end up helping disabled people with daily matters, such as shopping.

Kagiya also recommends that those facing physical or mental challenges utilize social media, such as the Line and Twitter apps. Social media can be accessed even during disasters, and it is crucial to stay in contact with neighbors, consultation experts and others.

“Help cards” should be placed inside emergency evacuation bags. These cards can be used to record such information as the details of holder’s disabilities and the kind of help they need. The cards can be obtained at local governments offices and from other entities.

Jun Suzurikawa, a wheelchair user and a senior official of the research institute of the National Rehabilitation Center for Persons with Disabilities in Saitama Prefecture, said: “People need to assume disasters [will occur], and make lists of items and services that will be needed at home, while traveling and when in shelters. By doing so, people will be less inclined to panic.”