August 19, 2022

ISLAMABAD – As temperatures rise and heatwave alerts intensify in Karachi, air-conditioners, coolers, and fans are switched on and markets for electrical cooling appliances flourish.

As researchers studying the impacts of extreme heat in urban Pakistan, we have been exploring what it means to profit from heat, which has become a pervasive and immersive experience for people living and working across South Asia.

Even though South Asian bodies are believed to be acclimatised to higher temperatures and humidity levels compared to their counterparts in the Global North, the increasing pace of global warming aided by human-caused climate change, is leading to unprecedented patterns in heat exposure for these populations.

Heatwaves have become more frequent, more intense, and last longer than in previous decades. When the temperature exceeds 45℃, it has already become physiologically impossible for people to continue everyday activities.

The main driver of increased heat exposure is a combination of global warming and population growth in already warm and densely built-up urban centres — our research at the Karachi Urban Lab shows that over the past 60 years, Karachi’s daytime temperature has already gone up by 1.6℃. This may be an effect of the urban heat island, caused directly by the city’s unchecked expansion, compaction, and densification.

The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) Sixth Assessment Report notes that the majority of the population exposed to heatwaves will live in urban centres. Extreme heat is a stealth killer and with Pakistan’s insufficient death registration system, it is highly likely that deaths related to extreme heat exposure go unreported (personal correspondence, KMC Deputy Director Graveyards).

Experts suggest that South Asia is the most affected region when it comes to heat stress, and certain populations — low income, migrants, elderly, homeless, people with underlying conditions, daily wagers — are disproportionately exposed to the climate-related health effects of urban heat islands and heatwaves. Moreover, the disproportionate increases of heat-related risks can also be attributed to their little or no access to contemporary cooling technologies such as ACs.

Raking in the profits

How does the demand for cooling technologies open up profit-making opportunities in Pakistan’s largest metropolis?

We have been looking at formal and informal markets for cooling appliances to understand how small-scale businesses play an essential role in delivering affordable, refurbished cooling technologies that are instrumental in shaping the rising demand for cooling in Karachi — a city of 25 million residents and where approximately 62 per cent live in informal settlements underserved by clean water and uninterrupted electricity.

The repair of cooling appliances such as second hand refrigerators, air coolers and ACs, is the cornerstone of livelihoods and profits in Karachi’s largest second-hand market for cooling technologies — the Jackson Market, established during British colonial rule. Named after Edward Jackson who was the Karachi Port engineer in the late 19th century, Jackson Market is where people from low-to-middle income households go to buy relatively affordable, refurbished ACs.

Refurbished window ACs for sale in Jackson Market. — Photo: Aqdas Fatima/ Karachi Urban Lab

Jackson Market is well-known for supplying ‘ship air conditioners’ that are portable devices used in smaller rooms in hostels and offices. These ACs are mostly Japanese manufactured, and were originally installed on ships. They reach the market as scavenged ‘scrap’ after ship-breaking processes. But recently, this supply route has shrunk, and such ACs now find their way into Karachi through Afghanistan.

Typically, a refurbished 1-ton wall AC sells for Rs15,000 to Rs20,000, and the price of a portable ship AC ranges from Rs10,000 to Rs12,000. The ACs are less costly when compared to new, branded ones such as a 1-ton PEL that costs Rs 83,000 to Rs 85,000 or a 1-ton Haier that sells for Rs 50,000. However, Karachi’s hot and humid weather takes a toll on all types of ACs, whether new or refurbished.

A shopkeeper explained:

Considering the intense humidity in Karachi, the life of ACs is usually not more than 1.5 years, regardless of the brand and price. An AC that sells for Rs100,000 has a life span that isn’t that different from a cheaper, refurbished one. The humidity in Karachi is terrible; it damages the ACs’ cooling coils. So, whether you buy an AC for Rs100,000 or Rs20,000, you still need to repair and maintain it regularly.

Wall ACs undergo functional checks in Jackson Market. — Photo: Aqdas Fatima/ Karachi Urban Lab

Even though disproportionately hotter and humid cities like Karachi present a challenge for environmentally and economically sustainable cooling technologies, with intensely rising temperatures, cooling is now no longer a luxury but a significant need.

Cooling as a necessity leads us to question who has access to cooling in conditions of extreme heat; a key point that aligns with the Sustainable Development Goal 7 (SDG7) — universal electricity access by 2030 that is critical for space cooling. Access to cooling is a major equity issue.

Access to power

Nearly 50 million people in Pakistan live without connection to the electricity grid and Pakistan also has some of the world’s worst power outages. Cities like Karachi suffer from prolonged power cuts that last between eight to 12 hours per day.

With urban heat islands and the onset of long, recurrent heatwaves, the role of domestic energy services is a prime concern for supporting indoor cooling spaces and mitigating the impacts of extreme heat. There is limited understanding in Pakistan of the ways in which urban households respond to or plan for extreme heat, and consequently how this might create greater demand for the cooling and air conditioning of indoor spaces.

The levels of inadequate indoor cooling among households with typically limited incomes, may be a strong deprivation element; those living in poverty, with inadequate access to electricity, and in housing with poor ventilation and materials and design that may be incompatible with certain cooling technologies, are often more vulnerable to extreme heat.

Globally, cooling related energy demand has tripled since 1990, and the demand for ACs is expected to dramatically increase in developing countries. Approximately 2 billion AC units are now in operation around the world and the demand for cooling has risen at an average pace of 4pc per year since 2000. This has significant implications for electricity grids.

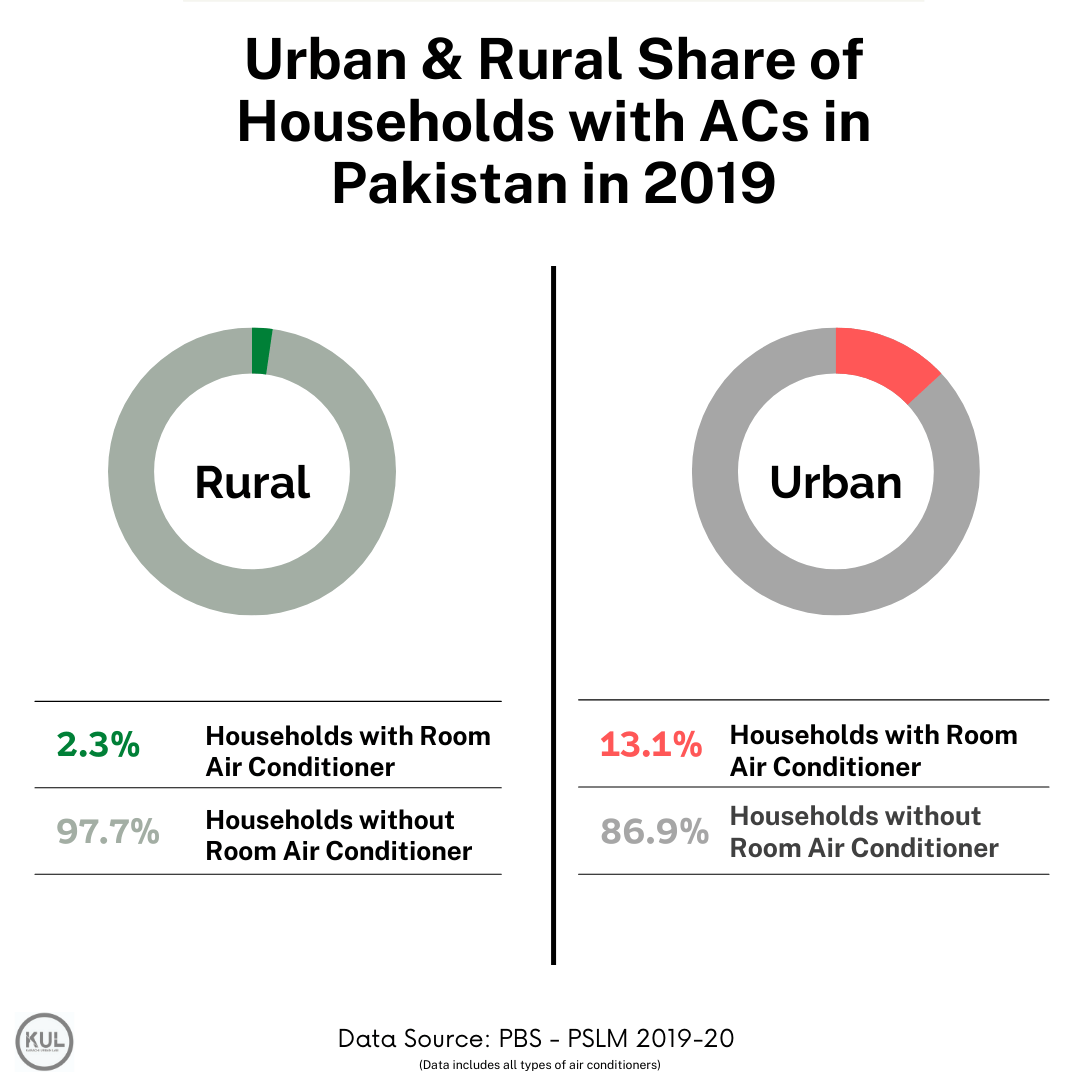

In hotter regions such as South Asia, the use of ACs is set to soar as incomes rise, populations grow, and urban centres continue to expand. However, many households cannot afford cooling systems. The ownership of ACs in Pakistan is relatively low: only 13.1pc of urban households own an AC and in the rural context, the share is considerably lower at 2.3pc as shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1 – Prepared by Karachi Urban Lab

Approximately 12pc of households in Karachi own an AC. But the demand for ACs is rising as people struggle to cool during hot weather, especially given that summers are arriving earlier and lasting longer.

As temperatures rise, cooling equipment vendors and traders see opportunities for business and profits. Vendors wait for the summer season to arrive so business can resume, and profits register upward trends. When the news channels announce heatwaves or an overall escalation in the city’s temperature, shopkeepers in Jackson Market anticipate increased sales.

A businessman explained:

We earn more during heatwaves. People demand ACs especially during heatwaves because they can’t sleep at night. People are so anxious that they are willing to buy a secondhand AC that hasn’t yet been fully refurbished. We double the price of every AC during heatwaves.

Portable ACs on display in Jackson Market. — Photo: Karachi Urban Lab

Suit your needs

Jackson Market offers a wide variety of ACs that meet the requirements of specific kinds of households and buildings, and each type of AC is categorised in terms of its voltage. For instance, a wall unit or window AC is suitable for small rooms. This type of AC is especially popular amongst families and individuals residing in apartment buildings. Most such clients prefer an AC that operates on minimal voltage, and this is due to their reliance on the kunda system — electricity connection that is secured through informal means.

A vendor pointed out:

Majority of the customers are from the middle- and lower-income groups, who can’t afford to pay rising electricity bills. To survive the heat, they secure electricity connections through the kunda system. These customers specifically request for ACs that function on low voltage and generate low electricity bills of Rs3000 per month.

The portable ship ACs are also cheap, but they run on high voltage and generate higher electricity bills of approximately Rs8,000 per month. Knowing that in Karachi we don’t have stable electricity connection and voltage flow, I wouldn’t suggest a portable AC to customers who rely on kunda system.

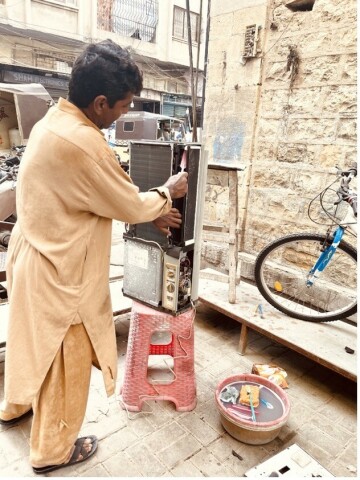

A laborer cleans a wall unit in Jackson Market. — Photo: Aqdas Fatima/ Karachi Urban Lab

Nearly all the second hand ACs are repaired and customised for new clients. Jackson Market is constantly busy with workers repairing, fixing, and remaking ACs before putting them up for sale. Businessmen employ labourers who clean or vacuum the old ACs; and skilled technicians perform functional checks and services. ACs that don’t function are separated and the spare parts reused for other mechanical devices.

When discussing the process of cleaning an old AC and the materials used, a labourer elaborated:

We use surf [detergent], a sponge, a dry cloth and silver spray that protects the metal. If the equipment has limescale stains, we use the silver spray for touch-up and repaint the scratches. People think water will disable the machine’s motor, but it doesn’t.

The repair work brings back to life the old ACs and adds value to the scrap materials that are identified as non-functioning parts. The vendors call this material electronic junk stock. All the non-usable parts of the ACs — from the coil and motor to the cards — are sold to the informal recycling industry at specific rates based on the type of material.

For instance, copper (tamba) is sold at Rs14,000 per kilogramme, plastic net at 700 per kg, and iron at Rs 95 per kg. These rates are set for the local kabari wallah who recycles the materials. If the material is sold in Karachi’s renowned recycling market — the Shershah Market, rates increase by at least Rs 20-30 per kg.

A big businessman explained:

I have electronic junk stock. In my business, we save everything until the season ends. Before the new season begins, we collect the entire junk and sell it to the kabari wallah. Every summer, I earn at least Rs1.2 million just from the junk that includes coil, compressor, metal, copper, and iron.

A small AC repair shop in Jackson Market. — Photos: Karachi Urban Lab

Extreme heat is a significant concern today from a health perspective, and the dominant discourse is correctly focused on the need to find sustainable solutions to mitigate risks in Pakistan.

However, we underscore the equally pressing concern about the need for cooling as a necessity that is shaped by the rising demand for ACs in cities like Karachi, where livelihoods and profits are deeply ensconced in the repair and maintenance of cooling equipment.

The profit making in places like the Jackson Market rests on an affordable market for cooling that serves the demands and needs of a city that is home to large and expanding low-income populations struggling with the impacts of extreme heat, and where the majority reside in informal settlements.

In our explorations about extreme heat and its impacts on the lives of poor, marginalised and vulnerable people in Pakistan’s urban centres, we understand the flourishing business in Jackson Market as part of the localised understanding of extreme heat where vendors and owners perceive it as a means of profit rather than a crisis to cope with.

In our broader research at the Karachi Urban Lab, we continue to explore low-income households’ cooling needs and the health impacts of indoor overheating, as well as the implications this may have on the adaptive capacities of urban Pakistan’s poor and vulnerable populations.