February 17, 2023

ISLAMABAD – The local government system is meant to resolve the small-scale, local issues faced by people living in a neighbourhood. It is premised on the belief that the problems that affect the day-to-day functioning of a community and its people may be solved more efficiently by those living in the said community.

Common sense dictates that these institutions can be made capable of providing fundamental services to people at the grass root level only by giving them the necessary authority and resources.

Common sense, however, seldom prevails in such matters.

The local body elections in Sindh were held on January 15, with the PPP emerging as the largest winner, gaining 93 seats and the Jamaati-i-Islami (JI) coming in a close second with 86 seats.

The JI and Pakistan Tehreek-i-Insaf (PTI) have accused the PPP of tampering with the results, with the former claiming that eight seats were “given” to the PPP. Amid the chaos, Karachi awaits the election of a mayor. Since no party has gained a clear majority, the results depend on cooperation and alliances between the JI, PPP and the PTI.

But Karachi’s civic issues won’t be fixed even if it gets a dedicated mayor, simply because of the way the system is currently configured. So how have we ended up here?

What is Article 140-A?

The 18th Amendment to the Constitution was aimed at decentralisation and the transfer of authority from the federal government to provincial and then to the municipal or local governments. What has happened since, however, is that provincial governments largely gate keep functions that are meant to be under the local government system.

Moreover, Article 140-A of the Constitution, which broadly speaks about the local government system, states: “Each province shall establish a local government system by law and devolve political, administrative, and financial responsibility and authority to the elected representatives of the local governments”.

Meanwhile, Article 32 of the Constitution states that “The State shall support local government institutions formed of elected representatives of the areas concerned, and special representation will be provided to peasants, workers, and women in such institutions.”

The reason for printing the exact words of Article 140-A above is to show you the stark contrast between what it states regarding the financial and administrative independence of the local government system and what is actually being applied as per the Sindh Local Government Act, passed in 2013, and its recent amendments from 2021.

Administrative powers of local government

The Sindh Local Government Ordinance 2001 (SLGO2001) envisaged a completely different administrative structure compared to what we see today. Back then, Karachi was considered a district and divided into 18 towns led by a ‘Nazim’ (mayor), with the local government being called the City District Government Karachi (CDGK).

In 2013, the Sindh government made amendments to the law, which came to be known as the Sindh Local Government Amendment, 2013 (SLGA2013) to divide administrative powers. The mayor was the head of the metropolitan corporation and the chairman in charge of the municipal corporation.

The local government commission itself was headed by the provincial minister for local government and mainly in charge for the restoration of the commissionerate system which empowers the province. In other words, the SLGA 2013 left the mayor with very little power.

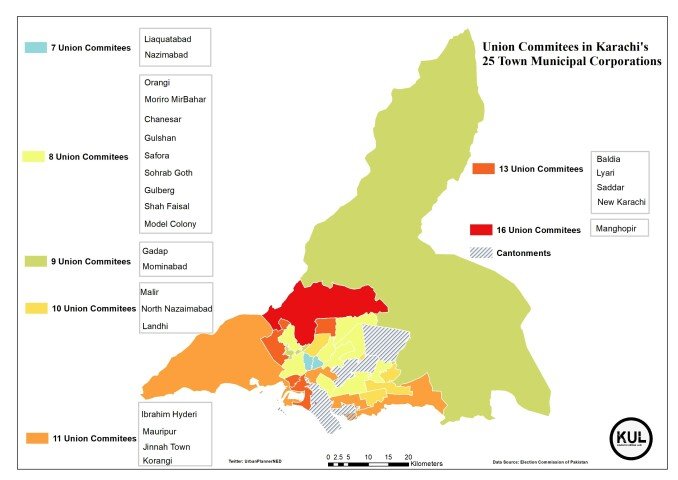

In recent amendments to the SLGA 2013, the Sindh government introduced the Sindh Local Government (Amendment) Bill, 2021 and replaced the word ‘district’ with ‘town’. It states that Karachi will now be divided into 25 towns, but in parallel, the seven districts will continue to exist. This raises questions about the administrative powers of Town Municipal Committees (TMC) and the chairpersons of TMCs against the seven deputy commissioners and 31 assistant commissioners across the city.

A map of the 25 towns in Karachi outlined in the SLGA Bill 2021 — Map visualisation by Karachi Urban Lab

Mayor’s role in the city

In 2001, all city government departments were subordinate to the city government. The CDGK was an authorised body that had the Karachi Water and Sewerage Board, Karachi Building Control Authority, Karachi Development Authority, Malir Development Authority, Lyari Development Authority and the Master Plan department under its control. The bureaucracy was also under the city nazim and the 18 town nazims in the absence of the commissionerate system.

With the promulgation of the SLGA 2013, however, many of the departments were taken away from the control of the city district government and the mayor of Karachi was left with very limited powers.

This was further limited under the Sindh Local Government (Amendment) Bill, 2021, leaving only even fewer functions for the mayor. These include road construction and maintenance, managing KMC hospitals and the Karachi Medical and Dental College, graveyards, parks, parking, public toilets, Karachi Zoo, Safari Park, Metropolitan Library, storm water drains, fire fighting, and anti-encroachment. Primary education and health were also taken away from local governments under the 2021 bill.

Distribution of union committees in Karachi’s Town Municipal Corporations — Map visualisation by Karachi Urban Lab

Local governance is key to effective administration as it is directly linked to the common man and grass-root level functioning. It is not enough to make the mayor the chairperson of Solid Waste Management Board (SSWMB) or Karachi Water and Sewerage Board (KWSB) if the chairman does not have any powers or even a budget.

The Constitution talks about empowering the mayor, but the Sindh Local Government (Amendment) Bill, 2021 has rendered the mayor’s position powerless. Ideally, the mayor should have jurisdiction over all city departments — be it solid waste, water and sewerage, or the building control authority. If the Sindh government is appointing the chairman of several departments, even if it is appointing the mayor, then who is really in charge?

Election of mayor and deputy

According to the SLGO 2001, the mayor and deputy were elected solely by a ‘show of hands,’ but this was changed in the early stages of the SLGA 2013, just before the election of the mayor and deputy. They would now be elected through ‘secret balloting,’ increasing the possibility of tampering with results.

The Karachi-based political party Muttahida Qaumi Movement (MQM) filed an appeal against this modification in the Sindh High Court. In its decision, the court ordered the provincial government to hold elections for mayor and deputy mayor solely by show of hands. The Sindh government acquiesced to the court’s directives when it passed the SLGA Amendment Act 2016, but with recent amendments in 2021, it has reverted to the secret balloting process despite the court order being in place.

Another issue with the 2021 amendment is its terminology. According to the Sindh Local Government (Amendment) Bill, 2021, “the council shall elect any person as mayor, deputy mayor, chairman, or vice-chairman.”

The word ‘any person’ is used instead of ‘any person in the house’, creating room for potential unelected persons to become mayors, deputy mayors, chairmen or vice chairmen. This proposed clause is contrary to Article 140-A of the Constitution which clearly mentions the word ‘elected representative’.

Protecting the Constitution, empowering local bodies

In 2022, the Supreme Court ordered the Sindh government to empower local governments as enshrined in the Constitution under Article 140-A.

The court announced this verdict in a petition filed by the MQM to the Supreme Court in 2013, seeking empowerment and autonomy for local governments in Sindh. It declared clauses 74 and 75 of the Sindh Local Government Act 2013 to be void. Under the clauses, the provincial government had the power to dissolve the local government at any time, and the power to take over any responsibility under the domain of local government.

While the SC’s verdict is a huge step in the right direction, there is a long way to go to in terms of its implementation.

What is needed is the implementation of Article 140-A of the Constitution in letter and spirit. For this, the provincial government must provide mechanisms and safeguards to local governments to ensure that their municipal functions are not snatched away from them whenever it deems fit and that they have the necessary powers and resources to resolve issues faced by their respective electorates.

Unless that happens, it won’t matter who gets the mayor’s slot — they’ll be powerless anyway.