February 16, 2023

ISLAMABAD – It is nearing rush hour along the Wall Street of Pakistan, better known as II Chundrigar Road. The traffic is a mix of pedestrians, cycles, motorcycles, rickety rickshaws, shiny cars, an odd donkey cart and a few buses, all trying to snake their way past each other.

Tapping her feet on the walkway outside the Burns Garden, Saiqa Aslam waits patiently. “It should be here any minute now,” says the 25-year-old.

After several minutes of honking and abrupt braking, a bright pink bus pulls up next to her extended arm. It has breathing space, empty seats and it is only for women — a rather unfamiliar sight in Karachi.

Aslam rushes to the door, which slides open to welcome her, the cool air from the AC drowning out the chaos of II Chundrigar Road. She grabs the green-coloured window seat at the back, glancing over onto the road, where a throng of men are trying to get onto a red bus — part of the People’s Bus Service.

Both the red and pink buses are part of the Sindh government’s recently launched Peoples Intra District Bus Service project, comprising of 240 buses that will transport passengers across Karachi.

“It is the first time I am travelling completely alone … it feels so freeing,” says Aslam, who is currently training to be a chef. She travels daily from Model Colony to II Chundrigar Road to attend training sessions at the Pearl Continental hotel. Previously, her father would accompany her on the commute to and from the hotel using the People’s Bus Service, which was launched a few weeks prior to the pink bus.

“The red bus was good, but a bus occupied only by women gives me a sense of safety,” says Aslam.

Safety is one factor that has stopped many like Aslam from chasing their dreams in the past. The idea of traveling in packed buses, struggling for space in the limited enclosure designated for women and having to bear snide comments from ogling men seems to have put off thousands of young women from seeking employment outside the sanctuary of their homes. In fact, women hardly make up 20 per cent of the workforce in Pakistan, despite making up half of the country’s population.

“Finding a place to sit inside the six-seat women’s compartment in the minibus was seldom possible,” says Zulekha Abdul Majeed, 60, a domestic worker. She is referring to the colourful buses that have been Karachi’s primary mode of public transport for aeons past. “Even if I did find space, the seat covers were often torn and through those spaces, the men tried to reach through to touch,” she adds.

The lack of mobility not only hindered women’s economic activities but also limited their social lives. “If I had the choice, I would never use the minibus. I don’t let my daughter get a job for the same reason. We get by on my salary — we don’t need anymore,” says Majeed.

These mobility woes finally saw some redressal on February 1, when the Sindh government launched the ‘People’s Pink Bus Service for Women’.

The inauguration ceremony at Frere Hall was attended by the who’s who among women in the government, entertainment, and corporate sectors. All hailed the project as a groundbreaking move towards making Karachi accessible for women.

Chronicles of the pink bus across Pakistan

This is not, however, Pakistan’s first attempt at setting up a dedicated bus service for women. Most have failed.

In 2004, Karachi got its first female-only bus initiative, comprising two buses that plied on different routes across the city. The project was closed down shortly after its inauguration.

Dr Noman Ahmed, Dean of Architecture and Urban Planning at NED University, recalls that “the female-only bus initiative in 2004 failed because of two reasons primarily: low frequency and missed timeline.” He went on to explain that the buses were not available at peak hours — the time they are intended for. The women were often left waiting for long hours, which created a disconnect and eventually led to the closure of the operations.

In 2012, a local bus company in Lahore launched a female-only bus service. A public-private partnership venture comprising three buses, this scheme too shut down after a short run of two years. “The venture was not commercially viable, hence when the government pulled back funding, the company halted its operations,” explains Lahore-based journalist, Shiraz Hasnat.

Similarly, the Sakura Women-Only Bus Service was launched in Abbottabad and Mardan in 2019 by the KP government. The project was funded by the Japanese government and facilitated by the United Nations Office for Project Services (UNOPS) and UN Women Pakistan. It only lasted a year.

“The main reason behind the failure of this project was contract violations,” says Sadaf Kamil, who was serving as communications officer at UNOPS at the time. “Operators did not run the buses on certified routes … they boarded male passengers and ran over their limit of daily mileage,” she adds.

The contracts were cancelled and despite several attempts to revive the project, the provincial government was unable to attract operators.

Eventually, the buses were handed over to the provincial higher education department, which in turn distributed them among various colleges and universities. The buses are now being used to fulfil the transportation needs of female students.

Thus, Pakistan has seen its fair share of failures when it comes to the provision of gender-based segregation in transport. However, not all is lost.

In October 2022, the government of Gilgit-Baltistan (GB) launched a women-only public transport scheme in 10 districts. The project is funded by the government and passengers travel free of cost.

“The facility has helped address the woes of women’s mobility in the region … the buses are filled to the brim each day,” Mohyuddin Ahmed Wani, GB’s Chief Secretary, told Dawn.com.

Wani explained that the buses run on a fixed route and operate only at peak hours, which has helped them limit the cost incurred to Rs20 million yearly. “This project has helped people reduce their [women’s] financial burden. We aim to run it free of cost for as long as we can.”

So is this the only way to make women-only buses a success? Keep them free or heavily subsidised?

Dr Ahmed advises against it. “It is just the same mistake repeated time and again,” he says. “The buses have been procured by the government and they’re running it on a subsidised cost. This is not a sustainable operational model … in the long term.”

Karachi’s pink bus

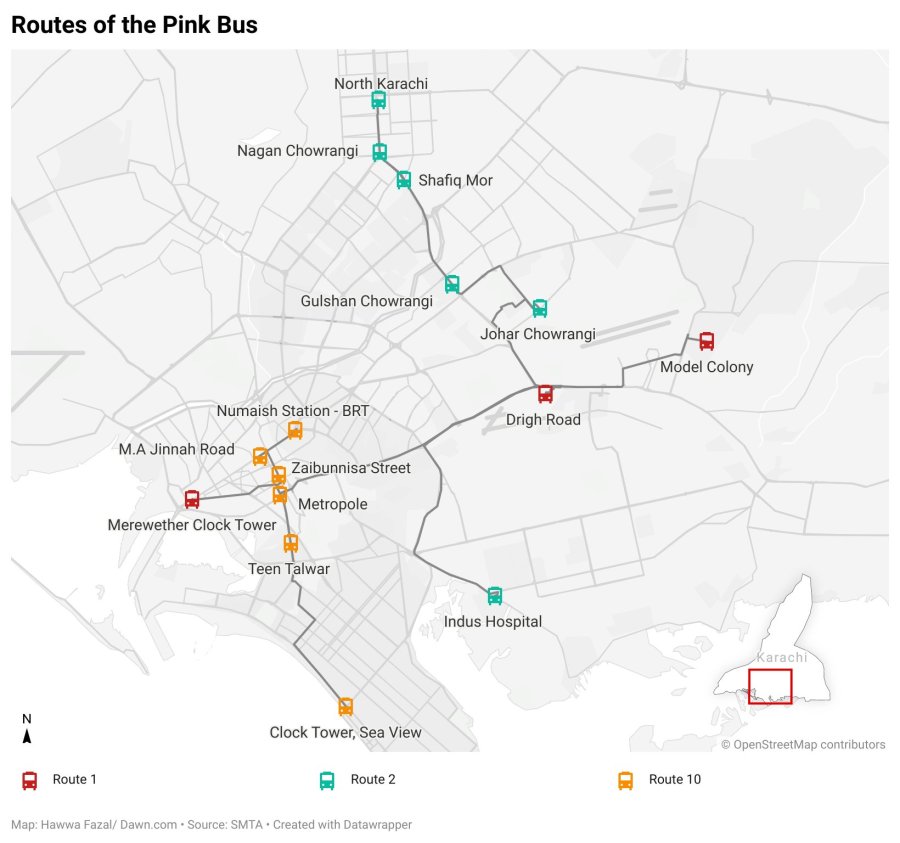

Currently, a fleet of eight buses is operating on only one route — from Model Colony to Merewether Tower via Sharea Faisal.

In a press conference on Monday, Sindh Minister for Transport and Mass Transit Sharjeel Inam Memon announced the launch of two new routes for the pink bus, starting from February 20.

The first new route will take the bus from Power Chowrangi in North Karachi to Indus Hospital via Nagan Chowrangi, Shafiq Mor, Gulshan Chowrangi, Johar Mor, COD, Sharea Faisal, Shah Faisal Colony, Sangar Chowrangi and Korangi No. 5.

The second, also known as route 10, runs from Numaish Chowrangi to Clock Tower via MA Jinnah Road, Zaibunnisa street, Hotel Metropol, Teen Talwar, Do Talwar, Abdullah Shah Ghazi and Dolmen Mall.

Moreover, he added that the number of buses on the current route would also be increased, while a similar initiative will be launched in Hyderabad on February 17. “There are also plans to launch the initiative in Larkana and Sukkur,” he added.

According to Sindh Mass Transit Authority (SMTA) Managing Director Zubair Channa, the buses will run during peak rush hours — 7:30am to 10:30am and 4pm to 8pm. Each bus has a capacity of 50 passengers — 26 standing and 24 seats. Two of the seats are dedicated for women with special needs.

“At rush hour, the number of female travellers is much higher than the capacity of the female compartment in the red bus,” explains Channa. “The pink bus is thus an attempt at addressing that issue”.

Wajahat Fatima, a smartly dressed woman on her way home after a long day of work at the shipping company says, “I was hesitant about leaving my van service despite the burden it put on my budget because of my joint pain. These seats were a huge sigh of relief,” says as she settles down on a seat, dedicated for disabled, located near the doors.

Prior to the pink bus, Fatima complained that she was unable to access the special seat in the red buses because they were occupied by able-bodied men who refused to leave the seat.

According to a 2015 study by the Urban Resource Centre in Karachi, women had to spend at least 10 per cent of their salary on transportation, which became a strain on their individual budgets.

“It’s much more affordable than the minibus,” says Kiran Javed, who works as a domestic help. “I used to pay Rs100 for each trip from Malir to II Chundrigar and back. Now, I pay Rs100 for both trips cumulatively,” she says, as she settles down on a seat at the front of the bus. “The subsidised cost has reduced my travelling costs by 50pc … these buses are a blessing,” she adds, the relief evident in her smile.

The pink bus is seen as a source of pride and a democratic space where women from all walks of life can sit together and reach their destinations in relative safety. — Photo by author

The subsidised fares — Rs50 for a complete trip — have been a blessing for many of the women who use public transport in the city. However, the subsidy may be short lived as, according to Transport Secretary Abdul Haleem Sheikh, the government may have to increase the fares soon in view of the rising fuel prices.

For his part, Channa believes the project is sustainable, even if the subsidies must be removed. The provincial government has signed a 10-year contract with the operators, in which they have to generate enough revenue to sustain the bus’ operations, he tells Dawn.com.

“This can only be done if the operators maintain the quality, comfort and keep it cost-effective, because the women always have the alternative to choose a private mode of transport that will drop them off at their doorstep.”

Seclusion in public spaces

Not everyone agrees, however, that the pink buses are the solution to women’s mobility woes in Karachi. Urban planner and researcher at Karachi’s Habib University, Sana Rizwan, cautions that while “the initiative may help increase female ridership and change household perception of public transport being unsafe for women”, all other factors such as policing, street lighting, safe bus stops, and changes in male mentality are vital for making public spaces and transport safer for women.

The researcher hopes that the change in perception will lead to an increased presence of women in the city’s public spaces, but what is required is a holistic system. “When it comes to transport, it’s not the segregated buses that matter, but the whole journey.”

Rizwan explained that that most women using the bus have to walk long distances to reach their offices and homes — some even have to hail a secondary ride to reach their destination. “The long walk to the bus stop causes mental and physical exhaustion.”

For this reason, Rizwan says, gender segregated services around the world have not worked, specially when it comes to public transit — none of them have reduced sexual harassment.

Ten-year-old Safia and her mother consider themselves lucky to have gotten seats on a bus in Karachi. — Photo by author

Some even see segregation of the sexes on public transport as regressive. “Female-only buses will not improve society, they will create a sense of fear,” stresses urban planner Mansoor Raza, adding that that the government needs to implement policies that strengthen the rule of law in public spaces. This would make coexistence of both genders possible and would be much better than introducing new buses on the already congested roads of Karachi.

Incomplete solution

For those traveling on the pink buses, however, the tangible gains far outweigh the hope for a long-term change. “When I travel in this bus, I feel at ease,” says Advocate Samia Ashraf.

The buses are seen as a source of pride and a democratic space where women from all walks of life can sit together and reach their destinations in relative safety. For 10-year-old Safia, who was traveling with her mother, simply getting a seat for herself on the bus was a blessing. “I actually got a seat for myself and I can see everything through the windows,” she says as she looks at the city’s sights passing by.

It’s a start, but it is incomplete.

The pink buses lack structure in terms of a reliable schedule and designated arrival and departure points. Women cannot identify where a bus stop is and often have to wait a long time before they can board a pink bus. The lack of street lighting too makes it a daunting task to wait for the bus.

According to a 2020 study, titled ‘Mobility from Lens of Gender’, by NGO Shehri-Citizens for a Better Environment, 58.3pc of blue-collar working women fear the long walk to the bus stop.

Aboard the pink buses, women also share horror stories of their encounters. “I was waiting for the bus yesterday, when two men came and stood behind me. I could feel their gaze on me,” says Faiza Ahmed. The bank employee said that she opted to use the red bus because waiting for the next pink one to arrive was not an option.

Travelling at night is another concern, with 40pc of women saying they avoid travelling after sunset, according to a 2015 study by the Asian Development Bank.

For engineering consultant, Ashar Lodhi, the pink bus is nothing more than a publicity project. “Women’s mobility with respect to sustainability should be more important than political mileage,” he says.

Meanwhile, the SMTA is “working on making bus stops,” says MD Channa. “The current route, however, passes through cantonment areas on which we can’t build without permission. We have asked the authorities and are waiting for approvals,” he adds.

How soon that happens remains to be seen. For now, the pink bus is being hailed by Karachi’s women as a welcome initiative. Only time will tell if continues its journey or becomes yet another relic among Pakistan’s archives of failed attempts at improving mobility for its women.