May 24, 2023

BEIJING – After China gave up its secrets on making silk, an ancient trade route was put to many other lucrative uses, report Deng Zhangyu and Li Yingqing in Kunming.

On a summer’s day in 1990, Chen Baoya and five friends embarked on a three-month hiking trip with horses, dogs and tents in which they would explore ancient roads between Yunnan province and the Tibet autonomous region.

The roads they used had formed a network linking China with the rest of the world for more than 1,000 years.

“Our plan was to do research on linguistics and culture along the ancient route,” says Chen, who with a few of the other team members were teachers at Yunnan University in Kunming, the provincial capital.

“One thing we discovered was that tea had been an important commodity along the route we trekked,” says Chen, now a professor of linguistics at Peking University.

Thus it was how the trekkers coined the term chama gudao, or the Ancient Tea Horse Road, to describe the route they had covered.

Su Guowen, leader of the Blang ethnic group in Pu’er, examines the tea leaves at his tea plantation. ZHANG WEI/CHINA DAILY

They set off from Zhongdian, or Shangri-La, in Yunnan in June, traveling over snowcapped mountains, valleys and grasslands at extremely high altitudes, reaching Chamdo in Tibet and Kangding in Sichuan province, before making the return trip and being back in Shangri-La in September.

During the trek, they met tea porters who worked for horse caravans. The scholars were told that these tea porters had traveled to India with horse and mule caravans along the ancient route.

In a published research paper on the trek, they used the name the Ancient Tea Horse Road, and it attracted a great deal of attention, helping generate further research in China and elsewhere.

The name was based on the common trade of tea for horses a millennium earlier, when Chinese needed the animals as they fought to ward off enemies in the north.

The network of roads became to be increasingly used in the Song (960-1279) and Yuan (1271-1368) dynasties and stretching through to the Ming (1368-1644) and Qing (1644-1911) dynasties.

“The route had once been called the South Silk Road,” Chen says. “But silk was not a necessity for most people, and the Silk Road linking China with the rest of the world was little used.”

Nevertheless, before the roads became conduits for tea, silk was the predominant, lucrative commodity carried along them, its destination being wealthy people in the West.

However, as the know-how of raising silkworms and making silk became implanted in many countries, they stopped buying it from China, meaning many of the Silk Road’s arteries fell into disuse.

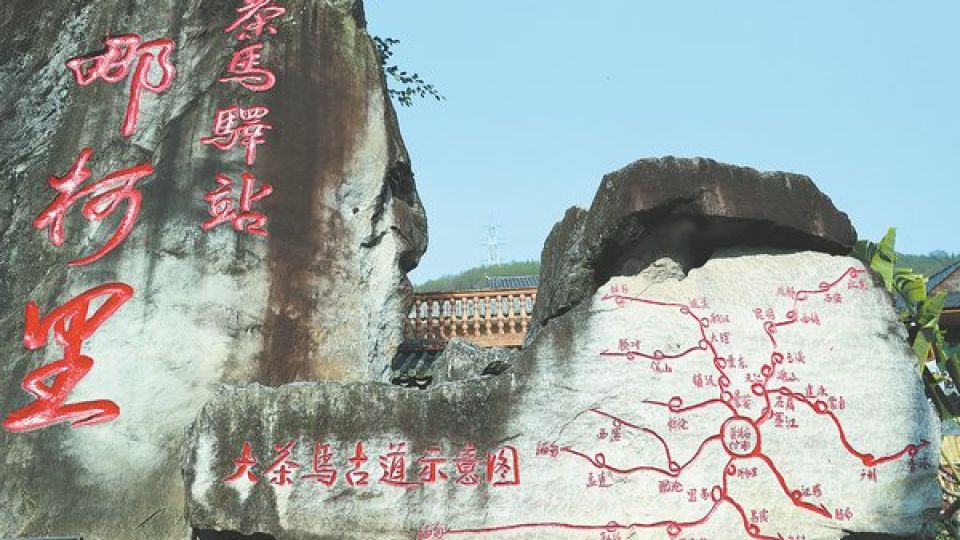

Nakeli used to be a stop that provided accommodation and horses for caravans and is now a tourist destination. ZHANG WEI/CHINA DAILY

“Only when the drinking of tea thrived during the Tang Dynasty (618-907) was the old trail reactivated and became a major commercial route between the East and the West,” says Chen, 67, who since the 1990 journey has never let up on his research.

He describes the route as a “life road” because the Tibetans living at high altitudes acquired a taste for tea in the Tang Dynasty, and it became a staple of their daily life.

However, because those mountainous areas are not conducive to tea growing, the long-distance tea trade began from Yunnan where tea trees were largely cultivated.

Tea produced in Yunnan was carried on the backs of horses, mules and even yaks into high-altitude areas, and to the south, including to what is now India, Laos, Myanmar, Thailand and Vietnam. It was also taken to the north, through the Xinjiang Uygur or Inner Mongolia autonomous region, to Russia.

“Russia is very cold and high-altitude,” Chen says.

“Tea grown in China was largely transported to Russia using the ancient route.”

Tea trees require a certain altitude, sunshine, humidity and particular soil types to grow, and those requirements kept the ancient road humming with trade for centuries.

Farmers working in Erlong Mountain, in Pu’er, where a large volume of China’s tea is produced. ZHANG WEI/CHINA DAILY

Su Guowen, 80, a Blang ethnic group leader in Jingmai Mountain in Pu’er, the main tea producing area in Yunnan, says that when he was a boy, he had to walk a long way to a tea trading market to sell tea with his family, from which horse caravans would take the commodity to South Asian countries.

“My father told me that there was an old tea trail more than 800 years old not far away from my village,” says Su, whose family has cultivated tea trees for 1,800 years according to the ethnic group’s records.

On the trail, horse hooves left deep indentations, round and deep in either the stone stairs or cobbled lanes. Marks of horseshoe prints and burned stones nearby are important tokens for Chen in identifying an ancient tea route.

“The caravans took little food with them. They cooked food during the commercial journey, and those burned stones are firm evidence of this.”

The trek was not just arduous but perilous, many tea porters never making the return journey.

Chen says that on his trek, his team encountered large wild animals, endured extreme weather, managed to avoid mud slides and struggled with the physical stresses of traveling at high altitude.

“When we got back to Shangri-La, many people were amazed that all six of us had returned in one piece,” Chen says.

Chen Baoya, one of the scholars who coined the phrase Ancient Tea Horse Road in 1990, with local children on his trek to the tea road. CHINA DAILY

Almost every year since that arduous trek, Chen has covered the same route, but in the relative luxury of a car. He has also visited Japan, Malaysia and South Korea doing research related to the tea route.

“Japanese people treat tea as an elegant lifestyle, while Tibetans in China treat it as a daily necessity,” says Chen, who spent a year in Japan as a visiting scholar in 2006.

In terms of linguistics, he says the word for tea in most places around the world derives from the Chinese cha.

“It’s just one more piece of evidence of how tea culture spread along the Ancient Tea Horse Road from China.”

Following tea culture, art produced by Buddhism, commodities including jewelry, jade, fragrance and ceramics have been exchanged along the most actively used international commercial route linking the East and the West.

In addition to that route, tea produced in China was eventually being exported from Zhejiang and Fujian provinces to Europe by sea.

“Both the ancient road and maritime routes helped transport Chinese tea and culture to the world,” Chen says.