June 26, 2023

BEIJING – When Li Xia and her 10-year-old son visited Shenzhen Museum in May, her son was attracted by an archaeological blind box that allows people to dig up the earth piece by piece and find their own treasures. The boy asked her mother to buy the blind box online as his birthday gift to experience the “excitement of being an archaeologist”.

“My boy spent a night digging up the box to turn himself into an ‘archaeologist’. He was so interested in the treasures hidden in it that he asked me to take him to visit the museum that produced the box later,” says Li.

The blind box that replicates archaeological digs is a star product designed by Hunan Museum in Changsha, Hunan province. Since its launch in 2021, it has become the most popular item at the museum’s online store. According to Zhang Lin, designer of the dig box, more than 50,000 such boxes have been sold on Taobao, a leading online platform.

“It offers a joyful way to re-create the experience of how archaeologists work on excavation sites. Most buyers are young people and children,” says Zhang.

With tools such as Luoyang shovels (an item often used at archaeological sites to take earth samples in China), brushes and gloves, people can follow the same steps as archaeologists do to find out their own treasures. The most interesting part lies in the unknown journey to discover what kind of treasure people would finally be digging out.

The blind box that replicates archaeological digs is a star product designed by Hunan Museum in Changsha, Hunan province. Since its launch in 2021, it has become the most popular item at the museum’s online store. According to Zhang Lin, designer of the dig box, more than 50,000 such boxes have been sold on Taobao, a leading online platform

All the archaeological discoveries are designed in a series of blind boxes. The treasures are small-sized replicas of cultural relics selected from Hunan Museum’s collections, such as bronze ware from the Shang Dynasty (c. 16th century-11th century BC), a pottery incense burner from the Han Dynasty (206 BC-AD 220) and a terracotta figurine from the Tang Dynasty (618-907).

“It provides a kind of spiritual satisfaction in a way for young people, such as applying cartoon images and illustrations into the making of the blind boxes,” says Zhang.

The warm welcome of archaeological dig boxes among young people has attracted lots of museums to enter into this field, making such kind of blind dig boxes in their own styles.

At a design competition of creative cultural products that more than 60 key museums across China participated in, which was held at Shenzhen Museum in June, various dig boxes were presented.

The Guangdong Museum in Guangzhou, Guangdong province, produces an underwater dig box to re-create the excavation of a ship lying in the ocean for hundreds of years, loaded full of porcelains that were being transported to the West. The Sanxingdui Museum in Guanghan, Sichuan province, replicates its sacrificial pits and hides treasures that duplicate its exotic-looking bronze and gold artifacts.

“Blind dig boxes are a unique creation of museums in China. They combine the hot concept of the blind box economy with archaeology. They’re interesting and full of uncertainty, and thus arouse people’s curiosity,” says Yang Mingyue, deputy director of the Beijing Institute of Culture Innovation and Communication with Beijing Normal University.

Henan Museum in Zhengzhou, Henan province, was the first in China to produce the dig box in 2019. It has made various series of dig boxes in the past few years. The sales of its dig boxes have reached up to more than 30 million yuan ($4.2 million), according to Wan Jie, Party chief of Henan Museum

Yang says the blind dig box is a good example of a museum product to arouse people’s passion to learn about archaeology, a subject that is often regarded as boring and hard to understand.

“Behind the small boxes are people’s respect for their millennia-long history and civilization. It also shows that the development of cultural products has entered into the phase of providing a joyful experience and involvement,” Yang adds.

Henan Museum in Zhengzhou, Henan province, was the first in China to produce the dig box in 2019. It has made various series of dig boxes in the past few years. The sales of its dig boxes have reached up to more than 30 million yuan ($4.2 million), according to Wan Jie, Party chief of Henan Museum.

Wan attributes the good revenue to young people’s love for this museum merchandise. More than 60 percent of their visitors are under the age of 35 and more than half of these young people are female.

Wan estimates that there will be more than 1.8 million visitors this year, under a daily cap of 10,000.Additionally, buying museum products is popular among young people.

“Young people love to buy items, especially through our online store. Some never have the chance to come to our museum, but they still buy our products,” says Wan.

Blind dig boxes are a unique creation of museums in China. They combine the hot concept of the blind box economy with archaeology. They’re interesting and full of uncertainty, and thus arouse people’s curiosity.

Yang Mingyue, deputy director of the Beijing Institute of Culture Innovation and Communication with Beijing Normal University

On one hand, a popular cultural product offers a chance for people to learn stories of those relics and treasures housed at the museum, and on the other, it has to be practical or can be used in daily life.

The most popular item in Henan Museum now is a series of jade-shaped lollipops. They are designed on a pair of jade pieces of a male face and a female face, which were unearthed in a couple’s tomb from the Spring and Autumn Period (770-476 BC).

To attract young people, the museum has set up a consultant team made up by various professionals to discuss their proposals for potential museum products. They have also collected data from the market to analyze their consumers’ favorites.

“We find that they are in pursuit of beautiful products. People’s appreciation for aesthetics has greatly improved,” says Wan.

Last year, they produced a doll wearing clothes in the Tang Dynasty style and posing like a flying apsaras from the Mogao Grottoes, which house one of the finest Buddhist art collections in China. The exquisite clothes are made using a traditional Chinese technique called qiasi, or wire inlaying, which uses metal wire to weave pattern on clothes or the surface of porcelain.

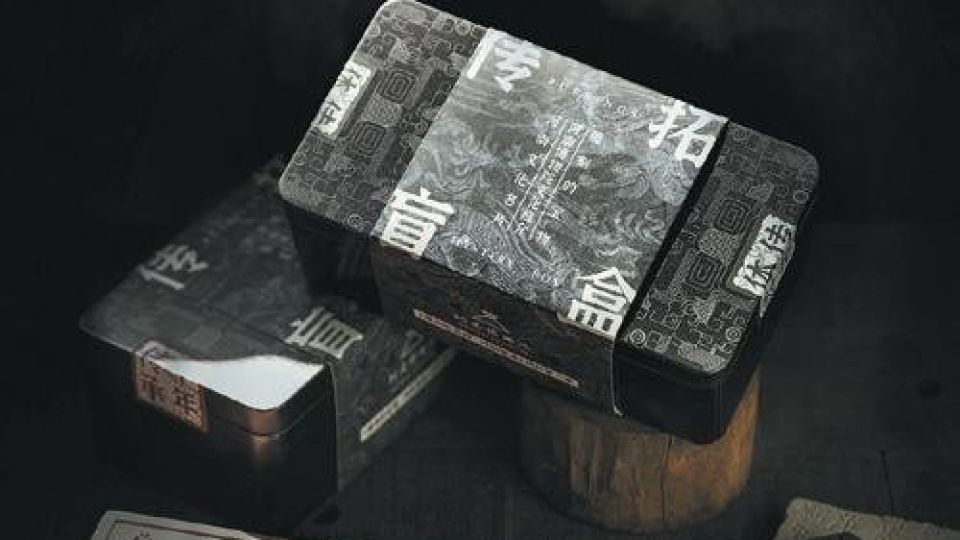

(Clockwise from top left) Visitors attend a show displaying popular cultural products designed by more than 60 leading museums across China at Shenzhen Museum in June; the art store of Suzhou Museum generates dozens of millions of yuan from its sales every year; items inside the boxes designed by Hunan Museum allow people to experience the thrill of excavation; the archaeological dig box made by the museum is a star product. (PHOTO PROVIDED TO CHINA DAILY)

When they showed the doll at the China Culture Center in Amiens, it received a warm welcome and hundreds of them were sold within a day.

Yang says that more and more museums have mixed intangible cultural heritage with their products to offer added value for consumers.

To attract young people, Henan Museum has set up a consultant team made up by various professionals to discuss their proposals for potential museum products. They have also collected data from the market to analyze their consumers’ favorites

“I think they are a perfect match. Techniques of intangible cultural heritage demonstrate China’s craftsmanship spirit and museum products show history and culture,” Yang says, explaining why so many cities currently are adding museum products onto their gift lists. Some have even been listed as national gifts for foreign celebrities.

“Such exquisite products can be seen as a demonstration of our country’s culture and image. From this point, cultural relics shoulder the mission to spread Chinese culture,” she adds.

Suzhou Museum in Suzhou, Jiangsu province, has long been known for its exquisite products. They have begun applying traditional techniques such as Suzhou embroidery, brocade from the Song Dynasty (960-1279) and kesi, a type of Chinese silk tapestry weaving that used to be enjoyed by royalty, into their products, such as bags, wallets and scarfs.

“These products are often priced at hundreds or thousands of yuan, a little bit expensive because we have to hire craftsmen to make them. But the price never influences their popularity among young people,” says Jiang Han, head of the cultural products department of Suzhou Museum.

The sales of cultural products at Suzhou Museum are doing well in the industry in China, ranking third after the Palace Museum and the British Museum, says Jiang.

Suzhou Museum in Suzhou, Jiangsu province, has long been known for its exquisite products. They have begun applying traditional techniques such as Suzhou embroidery, brocade from the Song Dynasty (960-1279) and kesi, a type of Chinese silk tapestry weaving that used to be enjoyed by royalty, into their products, such as bags, wallets and scarfs

Every year, the museum releases more than 200 products. All of them are based on the concept of “beauty and quality” to reflect the lifestyle of the literati in ancient times. Most of the museum’s collections are also related to things used by the literati in daily life.

One of the popular products is a series of vase-shaped fridge magnets. The colors are very Chinese-style and the shapes vivid. Although they’re small in size, they can really be used — people can put flowers into them by cutting them into the right sizes.

Various sizes of plush toy-style swords are also popular. The swords are designed according to a renowned sword used by Fuchai, king of Wu state in the Spring and Autumn Period about 2,500 years ago. Now it has been made into sword-shaped plush toy-style key chains and bigger-sized stuffed toys.

“We call it the ‘fat’ sword. The cute appearance draws lots of lovers. They use it to play with their cats or their friends to ease their pressure,” says Jiang.

She adds that the sword provides a kind of emotional experience for young people, and it builds up a connection with its users.

“The joyful experience and connection explains their popularity,” adds Jiang, estimating that the revenue of museum products will be more than 60 million yuan this year. About five million people come to visit every year.

To cater to young people’s appetite, the museum designed a role-playing board game based on the stories of four talented and renowned artists living in Jiangsu province 500 years ago, including painters Tang Yin and Wen Zhengming.

To cater to young people’s appetite, Suzhou Museum designed a role-playing board game based on the stories of four talented and renowned artists living in Jiangsu province 500 years ago, including painters Tang Yin and Wen Zhengming

Apart from selling the game, the museum has an exhibition room for people who are interested in the game to play it for free. Jiang says that, on weekends, the room is often booked out and full of children and young people.

“I think museum products in China can be competitive with their counterparts in the West in terms of creativity and variety. And China has the largest industry chain to produce them,” she says.

In the future, museum products can extend the concept of “physical things” to include experiences such as dance and performance, says Jiang.

Yang says the future trend of museum products is to break the barrier of space, allowing more cultural relics to reach people’s daily lives.

“Only by reaching people’s daily lives can these products influence our cultural memory and cultivate our aesthetics and love for our culture,” says Yang.