October 30, 2024

SEOUL – ‘Tis the season for all things eerie and macabre.

As jack-o’-lanterns cast their glow and costumed revelers share tales of ghosts and ghouls, it’s worth remembering that the thrill of supernatural horror isn’t unique to Western tradition.

While Halloween only caught on in South Korea in the late 90s via Western immigration and pop culture, Koreans have long nurtured their own rich supernatural tradition. Their folklore brims with spirits, demons and shape-shifting creatures that would give even the most seasoned trick-or-treater pause.

A land of spirits

Early Western missionaries to Korea in the late 19th century found themselves in a country where the supernatural wasn’t just a belief, but a way of life.

The spirits of the land, known as “gwisin,” weren’t picky about their haunting grounds. Trees, rocks, household items, and above all, the animals that roamed the woods – everything was fair game.

William Elliot Griffis’s “Corea: The Hermit Nation” (1882) devotes an entire chapter to what he terms “shamanism and mythical zoology.”

Though looking through the Orientalist lens typical of his time, Griffis did pick up on something key: how deeply Koreans feared and revered their supernatural beasts. Tigers, serpents, dragons, fish — all could host spirits of varying moods here.

But none has stuck in people’s minds quite like the fox.

In Korean folklore, a fox, after a thousand years, can grow nine tails and shapeshift into human form at will.

This fox-spirit lore, believed to have originated from ancient Chinese myths, took a darker turn in Korea. While Chinese and Japanese foxes can either be friends or foes, Korean foxes are known to bring nothing but doom. To become human, they must eat their way through human organs, particularly the liver, where traditional medicine says the soul resides.

Modern pop culture has softened these creatures quite a bit — the 2010 K-drama sensation “My Girlfriend is a Gumiho (nine-tailed fox)” or the game character Ahri in League of Legends presents them as cute, attractive tricksters. But make no mistake — their traditional versions weren’t nearly so friendly.

The Fox Sister: a family’s nightmare

Among fox tales here, none are as chilling as “The Fox Sister.” It isn’t your typical ghost story — it’s raw horror through and through.

The tale kicks off innocently when a father with three sons prays for a daughter, saying he’d take “even a fox.” These are words he’d come to regret.

As he wished, a beautiful girl arrives to the family, but as she grows up, strange things start happening. Cattle turn up dead in the night, brutally torn apart and, curiously, missing their organs.

One night, the youngest son sees something he can’t unsee: his beloved little sister, her arm coated with sesame oil, reaching into a living cow and devouring its liver raw. When he tells his father the next morning, the old man won’t hear of it. He kicks out his truth-telling son while the others keep quiet.

Years later, after starting a new life, the son decides to check on his family despite his wife’s warnings. She knows about magic and, sensing trouble ahead, gives him some enchanted bottles just in case.

Upon his arrival, the son finds the family home falling apart, his parents and brothers gone, and only his sister remaining.

During his stay, the son wakes up to a pure nightmare: the rice has turned to maggots, the kimchi to severed fingers, and there’s his sister, crouched over their dead brother, feasting on his liver.

“Just one more,” she hisses, “and I’ll be human.”

What follows is a wild chase, ending only when one of the magical bottles sets the fox-sister on fire.

Horror above morals

The fox sister story appears in different versions all over Korea. Some renditions have nine sons instead of three while others end with the surviving brother heading off to become a Buddhist monk — perhaps having had his fill of family drama for good.

The tale remains a childhood staple in Korea. Even today, it lives on through children’s picture books, with online bookstores carrying nearly a dozen different editions.

Most Korean folktales aim to teach lessons about karma and good behavior, but this one takes a different approach. It seeks to shock and terrify, without providing the typical “good deeds, you’ll be saved” resolution. The way it breaks from the usual moral-of-the-story pattern is a rarity in Korean storytelling.

Lee, a 47-year-old mom of two, recalled reading the tale with her kids a few years back when they were in their early teens.

“I thought I knew the story, but I didn’t. I was shocked at how it ended — with the once-beloved daughter killing her parents and siblings,” she said. “I expected them to be brought back to life in the end, but that never happened.”

For kids who loved a good scare, however, the story was pure gold. “It was always among the most borrowed books in our library,” one reader recalled.

Other readers shared with The Korea Herald their childhood memories of shuddering at the story, especially those who read editions with graphic descriptions of the fox-sister’s handiwork, like the 1997 edition from local publisher Borim Press.

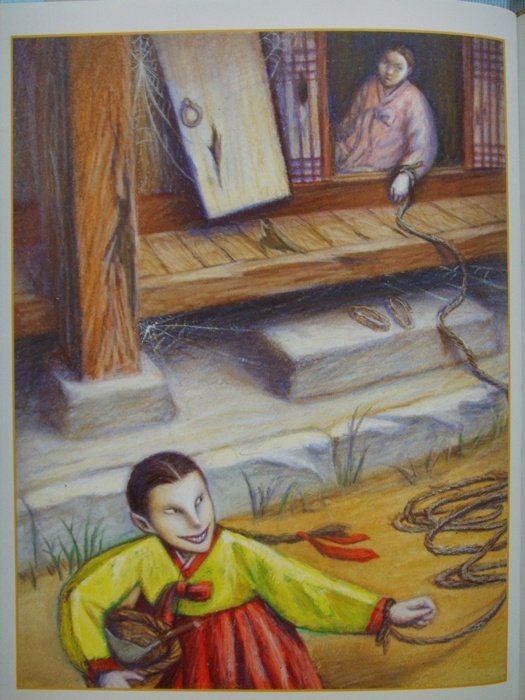

This version stands out for its eerie blue-purple tones throughout, and a spooky drawing of the fox-sister whose too-wide smile and slightly off-center eyes seem straight out of children’s nightmares.

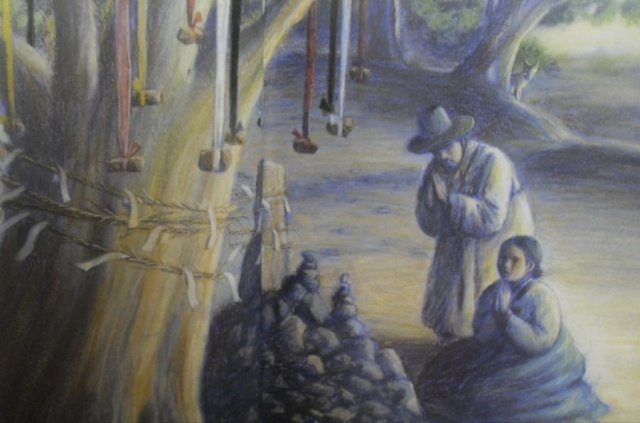

Pages from the children’s book “Fox Sister,” illustrated by Park Wan-sook and published by Borim Press in 1997. The book’s eerie illustrations left a lasting impression on a generation of young Korean readers who encountered them in their childhood. PHOTO: BORIM PRESS/THE KOREA HERALD

Pages from the children’s book “Fox Sister,” illustrated by Park Wan-sook and published by Borim Press in 1997. The book’s eerie illustrations left a lasting impression on a generation of young Korean readers who encountered them in their childhood. PHOTO: BORIM PRESS/THE KOREA HERALD

“I couldn’t even dare to look at it straight,” says Max Lee, 28, who first came across the book in kindergarten. “Those drawings just hit differently when you’re a little kid. I ended up scribbling all over the pages just so I wouldn’t have to see her face.”

He added that the illustrations terrify him even to this date.

Its flair for the grotesque isn’t the only thing that raises eyebrows. Some readers take issue with the story’s deeper implications. Bella Kim, 33, a graduate student, says she finds the tale’s gender politics troubling.

“Even as a kid, I picked up on how it sort of demonizes daughters,” she said. “The whole story simply reads like a warning against parents wanting girls.”