March 4, 2025

JAKARTA – Had it not been for the overeager and blundering police investigators in Central Java, the punk band Sukatani would remain somewhat unknown and their anti-cop song “Bayar Bayar Bayar” (Pay Pay Pay) might only be a curiosity item among followers of the duo.

But thanks to weeks of harassment from low-level police officers which culminated in the band removing the song from all streaming platforms, the song is now an instant hit and the subject of conversation of everyone who has access to the internet, inspiring dozens of covers and becoming a rallying cry for thousands of students who took to the streets in recent days to protest President Prabowo Subianto‘s austerity measures.

Even the internet’s most polarizing music critic Anthony Fantano was in on the action, as he published an online video defending the song.

The banning of “Bayar Bayar Bayar” is now a gold standard in what many term the “Streisand effect”, or when censorship delivers the opposite of its intended effect.

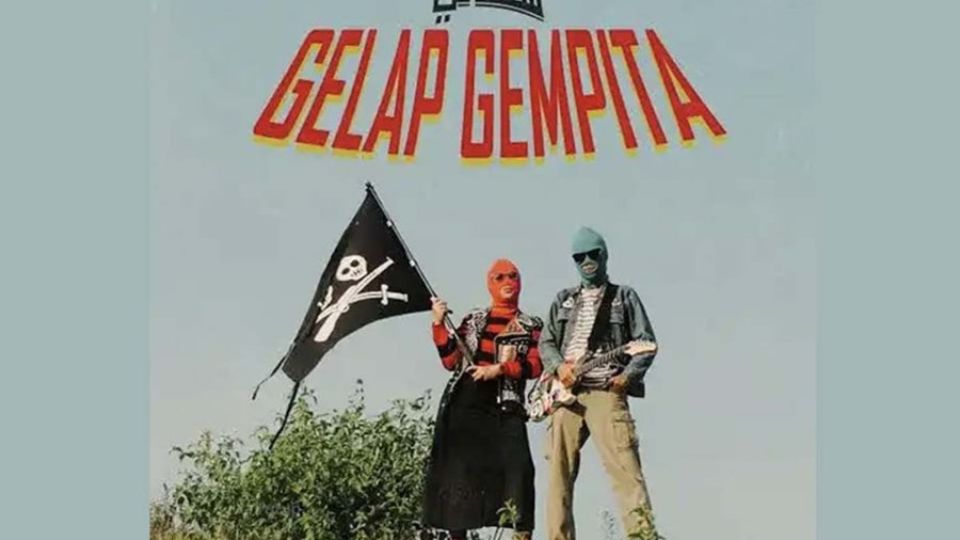

Yet, despite the setback in the police effort to ban the song from the brilliantly titled album Gelap Gempita (Dark Excited), the damage has already been done.

The police harassment resulted in what was effectively a doxing campaign that has taken its toll on the private lives of the two band members.

Sukatani’s members modeled themselves after the Russian punk trio Pussy Riot, a musical collective that delivered their performance as anonymous musicians donning masks and other regalia to hide their identity.

In a video apology –allegedly taped under duress– the duo was forced to deliver a mea culpa without their mask, effectively exposing their identity to the whole world.

Shortly after the publication of the video, the band’s singer Novi Citra Indayati was forced to resign from her job as an elementary school teacher in an Islamic school in Purbalingga.

On a more personal level, the police harassment must have been traumatic for Novi and her bandmate Muhammad Syifa al Lutfi, who were reported to be “missing” while on their way to Banyuwangi, East Java.

Sukatani’s ordeal is a clear reminder that even after 25 years of Reformasi, censorship remains a fact of life for artists, and while threats of censorship of music are a rarity under the current political situation, when it does occur, it can be as ugly as during the past authoritarian regime.

Under the New Order regime of General Soeharto, the state apparatus was constantly on the prowl looking for signs of dissent and could always find justification to crack down even on the opaquest form of protest.

Consider the case of the country’s most renowned folk singer Iwan Fals who spent 12 days inside a military detention center in Riau after performing a song titled Mbak Tini (Sister Tini). The song tells the story of a woman who fell into prostitution after being laid off from work. The tune was deemed to be an insult to Soeharto’s wife Siti Hartinah, known by the nickname Madame Tin.

In 1991, the Information Ministry refused to grant a permit for radio airplay for the song “Pak Tua” (Old Man) from the band Elpamas, believing that the song was a sly dig against the aging Soeharto.

But even with the best efforts of the New Order censorship machine, these songs remain popular, and singers like Iwan Fals were emboldened to write more pointed protest songs like “Bento,” and “Bongkar”, which later grew to become the anthem for a nationwide protest to topple Soeharto.

Songs, melodies and lyrics work in mysterious ways and any attempts at censorship will always fail.

Go listen to “Bayar Bayar Bayar” and you will find it hard not to be inspired by the duo’s bravery. It’s also a mightily catchy song.