January 6, 2023

SEOUL – This is the first installment of the three-part interview series exploring what experts believe should take place for S. Korea to better advance its interests, while resetting ties with Japan amid disputes. — Ed.

For too long, South Korea has misplaced hope in breakthroughs, while Japan has pursued small steps rather than giant leaps in ties. That is a lesson for Seoul to mirror Japan’s strategy to negotiate better as they seek to reset relations amid longtime historical disputes, according to Yuji Hosaka — a naturalized Japan-born Korean known for his decades-old campaign on dealing with Japan.

How the two Asian neighbors should bring closure to holding Japan responsible for its wartime crimes and compensating Korean victims, who suffered from sexual slavery or forced labor during World War II, have been at the center of a debate that is yet to be resolved.

For some time, Tokyo has always come out as self-righteous, accusing Seoul of failing to keep its end of the bargain as if that were the only roadblock hampering progress, Hosaka said in an interview with The Korea Herald.

This perception of South Korea failing to keep its end of the bargain, chiefly perpetuated by Japan, is nevertheless reinforced in part by an impatient Seoul overly reliant on the power of “grand political gestures” in the hope they would somehow lead to “breakthroughs.” However, that won’t happen, Hosaka asserted.

“Taking small steps, and consistently so, doesn’t mean backing down. It’s more powerful because it involves revisiting what has taken place between the two countries — be it letters of statements or deals the two countries shook hands on,” Hosaka said.

The political science professor who teaches at Sejong University immediately referred to the 2015 deal Korea and Japan reached to “finally and irreversibly” resolve the issue involving Korean “comfort women” — a Japanese euphemism for sex slaves.

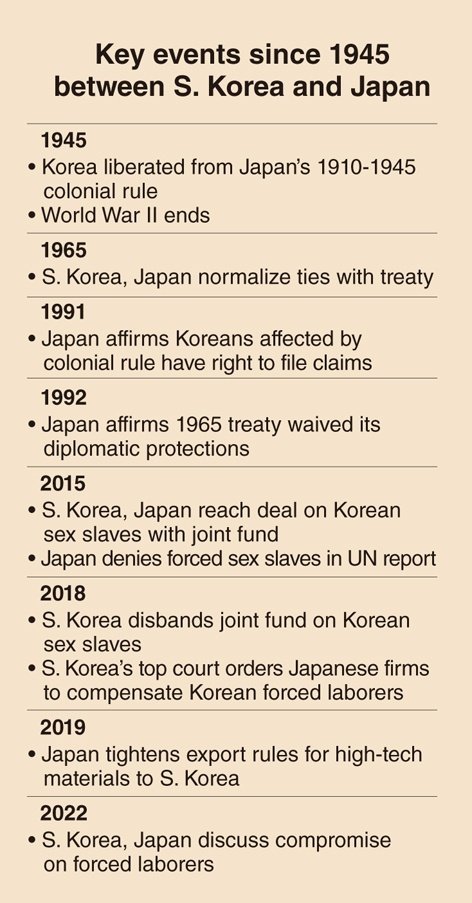

Calling the deal half-baked in serving the victims’ interests, Korea in 2018 dissolved a joint fund established through the deal to compensate the victims and support efforts to restore their “honor and dignity.” Since then, ties have dipped to a new low, with Japan blaming Korea for stepping back from the agreement.

“But if we really look at it, it was Japan that violated the deal,” Hosaka said, pointing to a report the Japanese government submitted to a United Nations panel shortly after the deal was sealed, saying neither its government nor military had forced women into sexual slavery.

The report, Hosaka noted, makes Japan guilty of breaking its word to help the victims reclaim their “honor and dignity.” This was the “premise” highlighted in the 2015 deal for the two countries to declare the sex slave issue resolved once and for all. The English copy of the agreement, available on Japan’s Foreign Ministry website, also acknowledges “involvement of the Japanese military authorities.”

“Doubling down on these kind of breaches is what constitutes powerful small steps that would eventually lend Korea the legitimacy and international backing to negotiate with Japan, from a position of strength,” Hosaka said.

Korea’s ever-shifting political landscape — something that tempts leaders to use their fresh political pull for a breakthrough in ties — consistently hinders singling out the inconsistencies championed by Japan. Such painstaking attention to detail, Hosaka added, could be a rather time-consuming job for a Korean president given only five years to leave his or her mark.

In some ways, the sex slave issue could prove to be much less of a headache than the forced labor dispute. South Korea and Japan could work to revive the 2015 deal by recommitting to the promises in it — however uninviting it may look, Hosaka said, referring to the other major obstacle fraying ties.

Fresh angle on wartime labor dispute

Unlike sex slaves, the forced labor settlement is a civil case, Hosaka contended, stressing that the Japanese companies accused of not compensating Korean laborers despite court orders here should meet with the victims in person to discuss redress.

The Korean and Japanese governments, currently working on a settlement behind closed doors, should back out and leave it to the firms and victims and their respective representatives, Hosaka said. The status quo could result in a repeat of the 2015 sex slave deal, where victims were sidelined and promises were hardly delivered.

The Korean government, rushing to end the labor dispute as quickly as possible before its political capital runs out, should look to “small steps” to make the new method workable, according to Hosaka.

The professor called on the Korean government to look at the year 1992, when the Japanese Foreign Ministry affirmed that the 1965 agreement, which normalized relations with Seoul, waived diplomatic protections. That means the Japanese government cannot intervene to protect its nationals, including firms, whose rights are threatened by another state. This is the kind of intervention Tokyo is currently pursuing, Hosaka said.

In 1991, the same ministry also found that Koreans affected by Japan’s 1910 to 1945 colonization of Korea still had the right to file claims. But Japan’s top officials, including current Prime Minister Fumio Kishida, have routinely and openly said those rights were terminated — another contradiction Hosaka believes Korea could use to turn the tables as it negotiates with Japan.

“The worry for now is this: Too many cooks, half-hearted measures and little satisfaction for every party involved,” Hosaka said, referring to the bilateral talks on the labor resolution. “The victims won’t just sit by with what they are given. A backlash, when and if followed, will replay a nightmare we know the ending to.”

Seoul’s Foreign Ministry said Wednesday it will hear public input on the issue starting Thursday next week, indicating the two countries are nearing a compromise while leaving room for last-minute changes. The Korean victims, however, are still visibly frustrated.

The victims are not really “in on what chief negotiators are discussing,” one victim said in a public statement, drawing an uncanny parallel seen years ago when the sex slave victims had entreated officials for a seat at the decision-making table.

Who is Yuji Hosaka?

Reducing the gap in the way South Korea and Japan understand their shared history to improve their strained ties has been a mission for Yuji Hosaka for the last 20 years. Hosaka is a political science professor who became a naturalized Korean in 2003 after earning his master’s degree and doctorate at Korea University. Born in Japan, he finished a bachelor’s degree at Tokyo University.

The assassination of Empress Myeongseong in 1895 by Japan, for example, is one of many blind spots for Japan when it comes to revisiting such shared memories, Hosaka said. He noted that removing such biases — so that Japan can properly make amends for using Korean sex slaves and forced laborers during World War II — is still a work in progress.

Helping foster peace in the Korean Peninsula is the eventual direction Hosaka sees his decades-old campaign on managing ties with Japan heading. Building peace in the peninsula is crucial not only for Northeast Asia but the Indo-Pacific — a region Hosaka says will be the next battleground for regional rivalry.

“I’ve been threatened and bullied, but that doesn’t and won’t stop me,” Hosaka said.