November 11, 2022

SEOUL – South Korea is set to reveal its long-awaited Indo-Pacific strategy this week, drawing attention to the course Seoul sees for itself as it navigates between the United States and China.

At the biannual Association of Southeast Asian Nations summit slated for Friday, South Korean President Yoon Suk-yeol is expected to present the country’s first diplomatic strategy for the Indo-Pacific. The presidential office said the strategy is the last piece of a puzzle to complete Yoon’s diplomatic policies.

“It is meaningful in that we are introducing our specialized version of the Indo-Pacific strategy centered on freedom, peace and prosperity. … I believe it (the strategy) will mark a historic milestone,” national security adviser Kim Sung-han said at a press briefing on Wednesday.

The US’ key partners such as Japan and European states laid out their diplomatic strategies for the Indo-Pacific region years ago, but South Korea has been slow to embrace one of its own. The strategic concept is largely aimed at containing China’s growing influence in the region.

But with China as South Korea’s biggest trading partner, previous South Korean administrations appeared hesitant to establish a regional strategy directly referring to the Indo-Pacific.

Asia as ‘Indo-Pacific’

The strategic concept tying the Indian and Pacific oceans together was first introduced by late former Japanese Prime Minister Shinzo Abe in 2007. This concept expanded the geographical demarcation of the Asian region to include India, a power deemed capable of containing China’s clout in the region.

Further elaborating the concept in 2016, Abe introduced the Free and Open Indo-Pacific strategy emphasizing values such as freedom, the rule of law and the market economy.

The FOIP concept gained regional influence when former US President Donald Trump adopted it to roll out its own Free and Open Indo-Pacific strategy in 2017 as its Asia-Pacific strategy. In May 2018, the US Department of Defense also renamed its US Pacific Command as the US Indo-Pacific Command.

US President Joe Biden also adopted the concept, releasing a FOIP strategy earlier this year. The Biden administration has been ramping up efforts to build stronger connections and establish group initiatives for the Indo-Pacific region.

The US’ allies and partners — including Australia, India and ASEAN countries — have also presented their Indo-Pacific strategies in past years. However, countries vary in how much their regional strategies align with that of the US.

Though it is a close ally of Washington, Seoul had been reticent on the Indo-Pacific concept. The former Moon Jae-in administration had introduced the New Southern Policy as its key regional strategy aimed at boosting ties with the ASEAN and India. However, it was largely perceived as a strategy for South Korea to avoid overly antagonizing China to mitigate potential vulnerabilities from Chinese economic coercion.

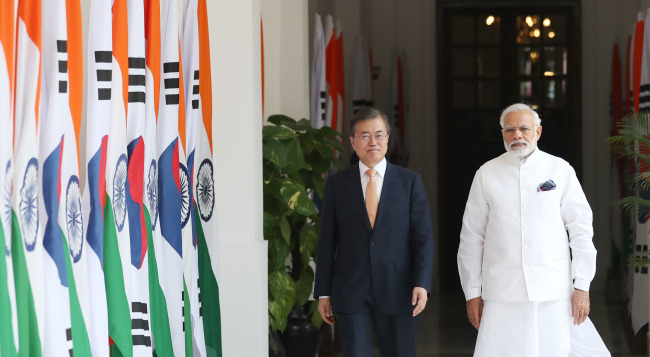

Former South Korean President Moon Jae-in (left) walks with Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi during a state visit to India from July 8 to 11 in 2018. (Yonhap)

Raising Indo-Pacific profile

In his first bilateral summit with President Biden in May — which took place only 11 days after his inauguration — South Korean President Yoon agreed to strengthen mutual cooperation with the US across the Indo-Pacific region.

Following the summit, Yoon announced he would formulate the country’s own Indo-Pacific strategy framework, and immediately established a task force at the Ministry of Foreign Affairs to create the draft, in May.

Under the Yoon administration, the country also joined in a number of US-led regional initiatives, such as the Indo-Pacific Economic Framework and the Chip 4 grouping of the world’s semiconductor powerhouses — all of which are largely deemed as efforts by the US to counterbalance China’s influence.

China has strongly criticized South Korea’s decisions, urging Seoul to “make its own independent decisions rather than be subjected to those made by Washington.”

The South Korean government maintains that its Indo-Pacific strategy would not be confrontational to a specific country.

“(The Indo-Pacific strategy) is not targeted at one specific country,” a Foreign Ministry official said under condition of anonymity when asked whether the strategy would be drafted in a similar direction to those of the US and Japan to keep China in check.

“The Indo-Pacific strategy we will present would be based on mutually reciprocal approach, and suggest the direction in which we can contribute to enhance freedom, peace and prosperity in the region,” the official said.

There may be some common factors the Korean strategy may share with other friendly nations, and the government will cooperate with the countries in those areas of common pursuit, the official added.

This compilation image shows President-elect Yoon Suk-yeol (right) and Chinese President Xi Jinping. (Yonhap)

Diplomacy for national interest

The plan outlined at the ASEAN summit Friday will be a broad outline, with the final draft expected around the end of this year, a Foreign Ministry official told The Korea Herald.

As “the last piece” of the Yoon administration’s diplomatic policy, according to South Korea’s national security adviser, the Indo-Pacific strategy is anticipated to show what position South Korea desires in the region, and how it would advance its role in international society.

Whether or not Korea’s Indo-Pacific strategy includes the concept of a Free and Open Indo-Pacific will be telling, observers say. As Seoul has recently been speaking out for peace and security of the Taiwan Strait with the US, promotion of the freedom of navigation in the envisioned strategy would also clarify Seoul’s position toward China.

Boosting regional connectivity with the ASEAN and Pacific islands, and increasing regional trade and investment are expected to be included. Common values such as freedom, peace and prosperity — all of which Yoon has stressed in his national speeches — are also likely be highlighted in the regional strategy, a Foreign Ministry official said.

Viewers see Seoul expanding its diplomatic influence in the Pacific region. In a foreign ministers’ meeting of Partners in the Blue Pacific, a US-led initiative to support the Pacific islands in September, South Korea joined as an observer. Seoul also plans to host an inaugural summit with Pacific island nations next year in Busan.

At the same time, there are concerns on how serious the Korean government is about its first regional strategy in the Indo-Pacific. The overall draft has been taken care of by the Indo-Pacific task force, temporarily launched under the North American Affairs Bureau in the Foreign Ministry.

While the ministry insisted that the task force works jointly with other bureaus and the presidential office to coordinate the strategy, some point out that the ministry has only deployed two working-level officials to oversee the draft of a national strategy.

Over Yoon’s introduction of the Indo-Pacific strategy, Shin Kak-soo, former vice foreign minister and ambassador to Japan, called it is a move to “normalize what has been abnormal.”

“South Korea is a core nation in the Indo-Pacific, and it does not make sense for the country not to have a diplomatic strategy for the region when even European countries have them,” Shin told The Korea Herald.

“As an Indo-Pacific country, (introducing the regional strategy) is an opportunity for South Korea to clarify its direction and position in the region where it has great interest.”

While maintaining ties with China is also important, it would be disappointing if South Korea’s Indo-Pacific strategy simply turns out to be similar to the former administration’s New Southern Policy with a “different wrapping paper,” said Go Myong-hyun, a senior fellow at the Asan Institute for Policy Studies.

“It might be risky for South Korea to embrace the confrontational attitude toward China as its allies and partners have done,” Go said. But the Indo-Pacific strategy should go beyond highlighting common values such as human rights, and include details which indicate the country’s policy direction, he added.