July 24, 2023

BANGKOK – Pumping his fist into the air, Mr Pita Limjaroenrat walked out of Parliament’s chambers on Wednesday in the midst of proceedings, while fellow party and coalition members stood in applause.

Moments before, the 42-year-old leader of the Move Forward Party (MFP) had said in his parting address: “I think Thailand has changed drastically since May 14. The people have already won half the battle, and there is still halfway to go.”

Maybe, his optimism was misplaced.

Mr Pita is under a temporary suspension of his parliamentary duties by the Constitutional Court pending its ruling over his ownership of media shares, which is forbidden under election law.

“I’ll be back,” Mr Pita wrote on social media shortly after leaving Parliament, even as lawmakers continued to debate whether he should get a second shot at the premiership.

But the reality was that he would not be back, at least not in his desired position as Thailand’s 30th Prime Minister. Later that evening, a majority of parliamentary voters denied him a second attempt at nomination for the post.

Now, his party is fighting for its place in the coalition it had assembled after winning the most seats in the May election. It has been a turbulent two months since the reformist MFP and its Ivy League-graduate leader shot to the top of the political arena, beating more established parties to bag 151 seats in the 500-member elected House of Representatives.

Its victory was powered by widespread desire for change, in a country that has experienced comparatively sluggish post-pandemic recovery, high household debt and more than a dozen military coups, with the most recent in 2014 by now-caretaker PM Prayut Chan-o-cha.

One female voter in her 60s, a former supporter of conservative parties who decided to throw her support behind the MFP this time around, said: “It’s about having new people in charge. I don’t necessarily support all the MFP’s policies, but something must change.”

With the backing of main coalition partner Pheu Thai and six smaller parties, the MFP entered uncharted territory as it tried to lead the 312-member alliance in establishing what it termed the “People’s Government”.

However, the legal threats as well as the entrenched conservative forces that oppose the party’s seemingly radical policies have meant challenges at every turn.

“We have to apologise to the people and frankly admit that they (those in power) do not want MFP to be a core party to form a government,” said MFP secretary-general Chaithawat Tulathon on Friday, noting that opposing voices have cited the party’s stance to amend Section 112 of the Criminal Code – the lese majeste law – and loyalty to the monarchy as reasons to block the party from Government House.

Move Forward Party leader Pita Limjaroenrat pumping his fist into the air as he leaves parliament chambers on July 19, 2023. PHOTO: MOVE FORWARD PARTY

On Friday, the MFP stepped back from leading the coalition to allow election runner-up Pheu Thai to head the bloc’s efforts in establishing the government and installing its chosen candidate as PM.

The events exposed MFP’s political naivete in thinking it could push through a progressive platform that has been rebuffed by conservative factions, said political scientist Punchada Sirivunnabood.

“You can believe strongly that the Senate has to respect the people’s votes, but when it comes to politics, in practice, you cannot be too idealistic,” she said, noting the party’s confidence before the first failed bid that it would get enough Senate votes – a crucial source of support – for Mr Pita to qualify as PM.

But Mr Pita was right about one thing – his party’s unexpected election victory presaged the winds of change in Thailand’s electorate. Insiders say that core party members themselves were “shocked” at the win, even as they saw MFP vote share climb the night of May 14.

And it wasn’t just the electoral map that was flush with orange, as the MFP secured seats in both urban and rural provinces, some of which had been, for decades, the strongholds of entrenched political dynasties.

The streets of Thailand were equally awash with MFP’s signature colour, as “Pita fever” set in and people flocked to the party’s victory rallies. Besides the sudden proliferation of MFP-orange merchandise, some businesses even offered discounts in celebration, for example with one restaurant pricing its popular “som tam” Thai salad at just 31 baht (S$1.20), in line with the party’s ballot registration number 31.

Thai media also reported that lottery tickets with numbers associated with the party, like 31, 30 (The next PM would be Thailand’s 30th) and 42 (Mr Pita’s age) were highly sought after.

A few supporters even began referring to Mr Pita as prime minister, both online and on the streets.

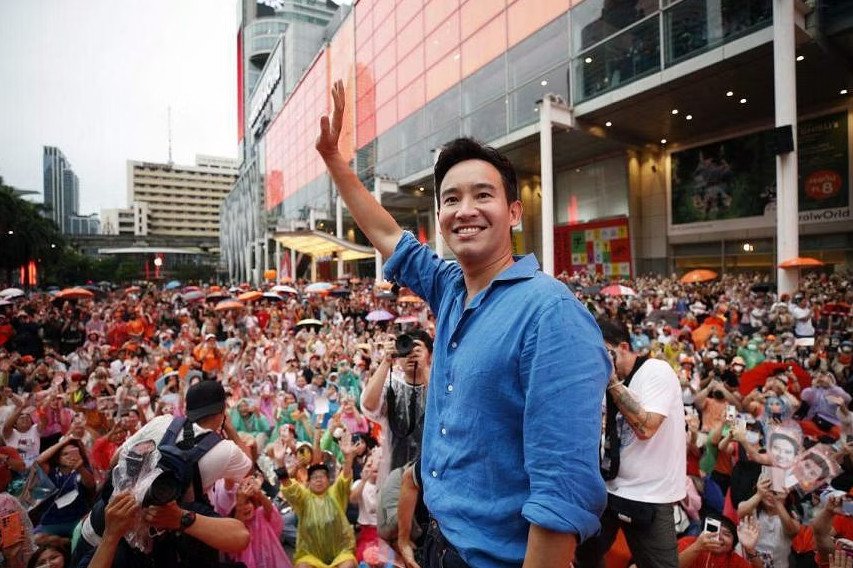

Move Forward Party leader Pita Limjaroenrat greeting supporters during a rally to thank voters in Bangkok on July 9, 2023. PHOTO: EPA-EFE

But it was never smooth sailing for the MFP. Calling the alliance between MFP and Pheu Thai an “unnatural” partnership, political analyst Ken Mathis Lohatepanont said their roughly similar number of seats – 151 and 141 respectively – set them up for friction.

Traditionally, the two largest election winners have competed to form governing coalitions.

Beneath the handshakes, fist bumps and finger hearts that MFP and Pheu Thai leaders displayed, the main partners in the eight-party coalition tussled for weeks over which would produce the House Speaker.

They finally reached a compromise on July 3, the eve of the vote, putting forward Mr Wan Muhamad Noor Matha, 79, of the Prachachat Party, a junior coalition member.

The veteran politician has held Cabinet positions in previous governments, including during the administration of the Thai Rak Thai, a predecessor of Pheu Thai.

Hints of regret over the partnership surfaced occasionally.

During the row over House Speaker, Pheu Thai leader Cholnan Srikaew termed the alliance an “arranged marriage” and said the party could not dash the hopes of pro-democracy voters, who expected them to stick together.

Without revealing who he had voted for, businessman Tanarit Sakulyanontvittaya, 44, said he had voted for a party he hoped would bring “a new future”. “Let the new generations of politicians try this out, because the old people have done this for very long,” he said.

But winning the most seats or gathering a majority coalition in the Lower House is no guarantee of leading a government. Candidates vying for the premiership must receive majority approval from both the 500-elected MPs and the 250-member Senate.

The MFP’s anti-establishment policies, such as plans to amend the lese-majeste law and reform powerful establishments like the military and monopolistic industries, have faced resistance from conservative and royalist forces.

Some senators and non-allied politicians have argued that the changes proposed by MFP would undermine the monarchy and national security.

Still, the MFP has repeatedly insisted it will not back down from its goals, including to lessen the severity of the lese-majeste law, which critics say is misused to clamp down on free speech.

Having prided itself on its clear and uncompromising message on democratic ideals, the MFP will find it difficult to walk back on key election promises, and risk losing its core supporters.

“If MFP gives it up its plan to amend section 112, they will lose their core supporters,” said Dr Punchada, who suggests that the MFP could tone down on its 112 campaign, or suggest new laws that will prevent the misuse of the law. “This might make it more acceptable and not severely change their message,” she said.

The party itself stemmed from the now-defunct Future Forward Party, which was dissolved in 2020 after the Constitutional Court found it to have violated electoral finance rules. While core Future Forward members like firebrand leader Thanathorn Juangroongruangkit were barred from politics, about 50 of its remaining MPs regrouped as MFP, with Mr Pita as their leader.

Dropping its radical policies might not be a panacea for its problems as there are already pending legal cases against the MFP and Mr Pita that could potentially lead to their removal from politics.

Pheu Thai is racing to gain sufficient votes from non-allied MPs and the Senate before the next parliamentary vote to choose a PM on July 27, and analysts think it may jettison the MFP to secure crucial votes from conservative parties.

A handful of parties that can provide it support have indicated that they will not approve a Pheu Thai-led coalition if the MFP remains part of it.

Soon after the MFP handed over the baton to lead the coalition on Friday, Pheu Thai’s Dr Cholnan said it would try to win over the Senate and other parties by negotiating and tackling their concerns, including the MFP’s stance on section 112.

But if their efforts fail, he said that there are options to exclude “certain” parties, and it is permissible for Pheu Thai to pursue alternatives outside the coalition.

Pheu Thai Party leader Cholnan Srikaew said his party would try to win over the Senate and other parties by negotiating and tackling their concerns. PHOTO: EPA-EFE

“There is evidence that Pheu Thai is willing to make deals across the aisle in a way that the MFP is not,” said Mr Ken.

Over the weekend, Pheu Thai held marathon meetings with a few conservative parties, including the Bhumjaithai Party (71 MPs), and outgoing PM Prayut Chan-o-cha’s former party the United Thai Nation Party (36 MPs).

Emerging from talks on Saturday, Bhumjaithai leader Anutin Charnvirakul, a deputy PM and the Minister of Public Health in the outgoing government, remained firm it would not work with a coalition that included the MFP.

With pressure building to resolve the political stalemate, the MFP could see itself back in the opposition camp, but this might not be the worst thing for the party.

Given their track record in scrutinising the Prayut-administration and the hurdles they’ve faced in the past months, they could easily return stronger and with a higher voter share in the next election cycle, said Dr Punchada.

On Friday evening, looking less chipper than he had in previous video addresses, Mr Pita said that while he failed in his bid to become PM, the hope to change the country had not ended.

He said the MFP would support Pheu Thai in forming a government for the people and that as long as the coalition members “hold tight” together, they could prevent the influence of the former military powers.

“Thailand has come a long way, and will never be the same as before. We won’t let them turn the country back in time,” he said.